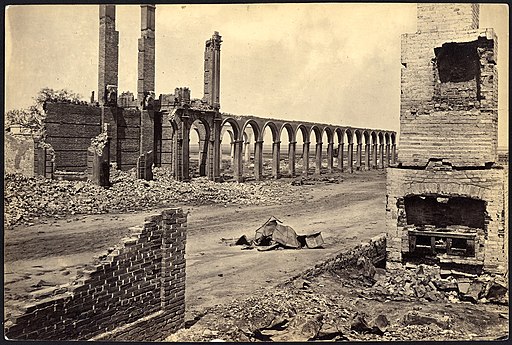

NORTHEASTERN RAILROAD DEPOT

Eyewitnesses to History

“I … was put in charge of a detail of about 75 men to load what cars we could ahead of us. We had not been out of the depot long before the women and children rushed in to see what they could get. The depot was filled with powder and explosives and caught on fire and was blown up—causing the most pitiful sight I saw during the war. Women and children, about 250, were killed and wounded, and some were carried out by where [we] were in line on the streets, with their clothing burned off and badly mutilated.” – Lt. Moses Lipscomb Wood, Company F, 15th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment, looking back from the departing train.

One can only imagine what the night of February 17, 1865, must have been like in Charleston. Having withstood Federal bombardment for four long years, it was finally clear – even to the rebellious Charlestonians – that the war was lost. When the last Confederate troops evacuated the city that night, Charleston went down in a so-called blaze of glory – and much of that blaze was caused by a terrible accident at Northeastern Railroad’s Wilmington Depot.

As he marched from Savannah to the capital city of Columbia, Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman cut two of the state’s three railroad lines, leaving the Northeastern line out of Charleston as the only hope for a Confederate retreat. Believing that saving troops that could join up with other forces later was more critical than saving a city that seemed undefendable, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard ordered an immediate evacuation of remaining Confederate troops.

The order specified they were to leave nothing behind that could aid the enemy when the city fell. Ships were scuttled, ordnance destroyed, and warehouses full of supplies and cotton torched. Retreating Confederates set fire to the Ashley River bridge, which raced out of control on the city’s northwestern edge. Fire was everywhere and spreading quickly. Troops moved remaining supplies to the Wilmington Depot on the city’s east side for evacuation. Between 8 and 9 a.m. on February 18, the last train pulled out, loaded with all the soldiers, supplies and ammunition it could hold.

As the train pulled away, hundreds of starving civilians, mostly women and children, dodged piles of burning debris to reach the depot, desperately seeking any remaining food and supplies. They did not know that one room still held about 200 forgotten kegs of gunpowder.

Survivor Pauline Dufort, who had spent the night trying to protect her family on Meeting Street, vividly recalled what happened next: “… there came another terrible explosion - louder than any yet - the smoke of which darkened the sun as its hideous folds curled skyward. It was the Northeastern Railroad depot that had been blown up, and with it a number of persons who had gathered there in search of provisions. Some were killed outright and their mangled bodies and limbs were scattered and buried under the burning ruins.”

Only the tracks and rubble remained.

Eyewitness to History

“The people rushed in to obtain the supplies. Several hundred men, women, and children were in the building when the flames reached the ammunition and the fearful explosion took place, lifting up the roof and bursting out the walls, and scattering bricks, timbers, tiles, beams, through the air; shells crashed through the panic-stricken crowd, followed by the shrieks and groans of the mangled victims lying helpless in the flames, burning to cinders in the all-devouring element.” – Charles Carleton Coffin, war correspondent, Boston Journal

“The rebel commissary depot was blown up, and with it, it is estimated, that not less than 200 human beings, most of whom were women and children, were blown to atoms.” – Lt. Col. Augustus G. Bennett, 21st U.S. Colored Troops

“… a tremendous explosion which shook the city to its very foundation brought us to a halt. Crowds of frightened women and children, white and black, came running toward us, some of them saying, ‘Don’t go there,’ ‘you’ll be blown to pieces.’” – Survivor Pauline Dufort