CHARLESTON'S PUBLIC SQUARE:

HELL, WICKED PLACES & SOME REALLY GREAT JAZZ

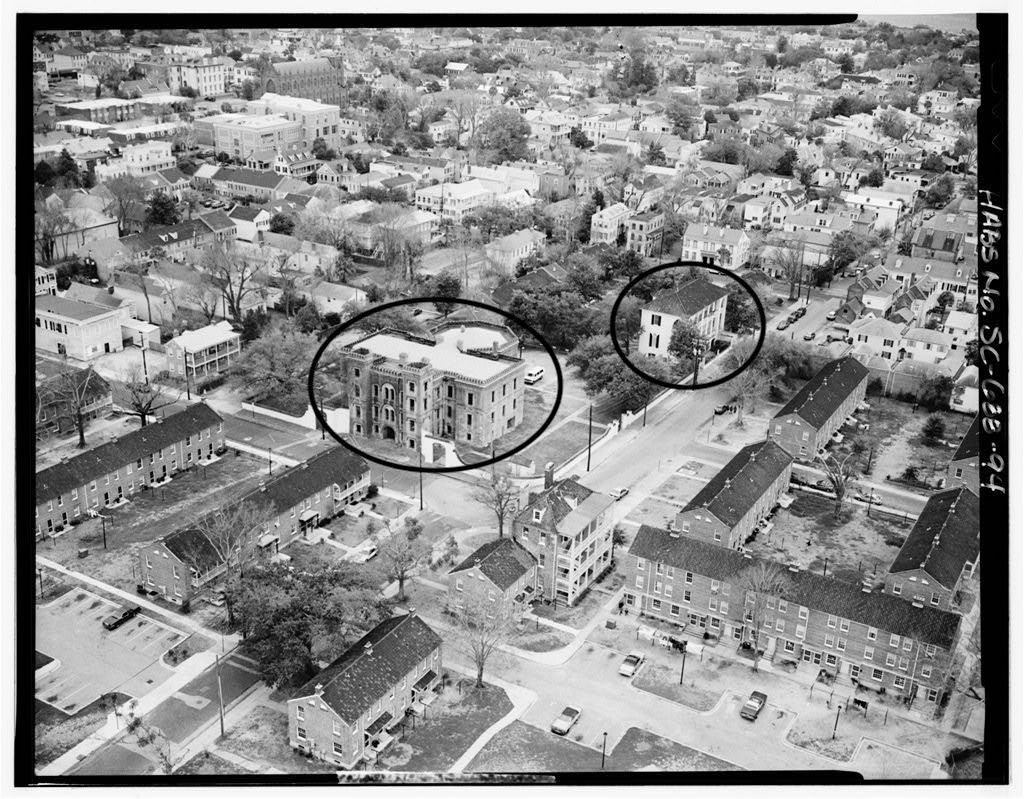

No other spot within Charleston’s Old and Historic District has crueler or more inhumane stories to tell than a small, unassuming block located almost in the center of the peninsular city, bounded today by Magazine, Logan, Queen and Franklin streets. Many have claimed to sense the cold aura of death, despair and hopelessness emanating from this relatively unattractive parcel of land tucked amid downtown’s beautiful gardens and streetscapes, even those who are unfamiliar with its history. Something of that legacy carries over even into today, as the historic buildings that remain on this site abut an urban public housing project built in 1939.

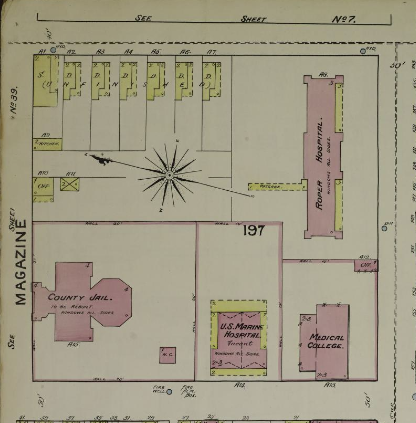

Untold thousands have suffered and died within this four-acre parcel. Many of their bones lie subterraneously here, unceremoniously interred in unmarked graves on land designated for public use by Lord Proprietor Anthony Ashley Cooper and his secretary John Locke in their 1680 “Grande Modell of Charles Town.” Here, not too far outside the early colony’s fortified walls, Cooper and Locke set aside public land that would one day house a jail, a poor house for debtors, a workhouse for the enslaved, a hospital, a lunatic asylum, a paupers’ graveyard, and a powder magazine.

Shortly after the colonists moved from their original settlement at Albemarle Point to today’s peninsular city in 1680, the lot began being used as a public cemetery.1 Yet as the colonists began building new churches, first St. Philip’s Anglican in 1680 and the Dissenters’ Meeting House the year thereafter, families increasingly buried their dead in the hallowed grounds of their respective churchyards. In addition, as plantations developed many of Charles Town’s planters’ aristocracy, as well as their enslaved workers, were buried in family cemeteries on their estates.

As more colonists began to be buried elsewhere, the need for the public cemetery decreased and it became used primarily for the interment of “strangers,” mariners and visitors from out of town or anyone who did not have a local church affiliation. As use of the old cemetery waned, it also became less well maintained. In November 1743, a grand jury complained to the provincial government “that ye Old Church Yard, or burying place in Charles Town is very much neglected and that all manner of filth, & nastyness is thrown into the graves and vaults of the deceased, whereby the surviving relations of the deceased are very much troubled and grieved.” 2

As use of the public cemetery decreased, Charles Town’s Provincial Assembly began to construct public facilities upon the block, undoutedly right over the graves of many long buried and forgotten there. The first of these was a new powder magazine completed in 1737 on its northwest corner. Though this magazine remained there for only a couple of years, its presence is recalled in the name of the block’s northern boundary, Magazine Street.

A facility to house the poor and homeless was completed a year later on the plat’s northeastern corner. Before the American Revolution, the Church of England was South Carolina’s officially sanctioned state church and as such it was largely responsible for the care and welfare of orphans, the poor, and those deemed insane or disabled. Church members would either take in these wretched souls themselves or hire someone to provide them with the basics of shelter, food, water and clothing.

Before 1738, however, a grand jury in Charles Town determined that “private dwellings rented for the sick and poor were inadequate, dilapidated, and costly,” leading to the establishment of a building to house the poor and “to punish idle and disorderly people,” providing “a controlled environment to regulate the morals of the uninhibited.” 3 The first building constructed for this purpose was completed in 1738, however it was replaced within 30 years because of “putrid smells, filthy, crowded rooms and indiscriminate mixing of poor widows, prostitutes, and thieves,was unfit for human occupancy.” 4

In 1746, the Assembly rebuilt the powder magazine, this time closer to the center of the property, as well as new military barracks on the magazine’s original northwest corner site.

When the city fell to the British in 1780, Charlestonians were ordered to surrender their weapons, which were to be stored in a supporting building of the magazine. Historian Christine Trebellas notes the British carelessly gathered “‘...guns, fowling pieces, rifles, muskets, pistols, all crammed to the muzzle with the remaining cartridges of their late proprietors … cartridge-boxes, powder-horns, all recklessly into one heap.’ The result was an explosion which shook the city to its foundation. The blast destroyed the magazine, the poorhouse, the guardhouse, the barracks, and the arsenal, and killed most of the soldiers and civilians in the area." Bodies were found hurled against the walls of both the Unitarian Church on Archdale Street [a full block away].” 5 According to accounts found during Trebellas’s research, about 200 people were killed; six residences and a brothel were destroyed.

The poorhouse was rebuilt along the Mazyck Street (now Logan Street) side of the lot. Those deemed insane were kept separately from the poor in this new three-story building.

A district jail and workhouse for the enslaved were added in 1802 - 1803, as was a new asylum for the insane in 1822. Two years later, members of the Medical Society of South Carolina, founded in 1789 to “improve the Science of Medicine, promoting liberality in the Profession, and Harmony amongst the Practitioners in this City,” constructed the Medical College of South Carolina, predecessor to today’s Medical University of South Carolina, behind the District Jail on the block’s southwest corner. 6

In 1826 Robert Mills, generally credited with being America’s first native architect, described these public institutions in his Statistics of South Carolina: “Lunatic Asylum – This benevolent institution was founded in 1822; the building is now ready for the reception of patients; it will contain 150, nearly all in separate rooms; the plan of the building is such as to admit of any extension, without departure from the original design … The original act of Legislature making appropriations for a Lunatic Asylum including also an Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb … The public prison is situated on Magazine Street … It is a large three-story brick building with very roomy and comfortable accommodations … There has been lately added to it a four-story wing building, devoted exclusively to the confinement of criminals. It is divided into solitary cells, one for each criminal, and the whole made general fire proof. A spacious court is attached …Very good health is enjoyed by the prisoners. The work house, adjoining the jail is appropriated entirely to the confinement and punishment of slaves. These were formerly compelled only occasionally to work; no means then existing of employing them regularly and effectively. The last year the City Council ordered the erection of a tread-mill; this has proved a valuable appendage to the prison, and will supercede every other species of punishment there." 7

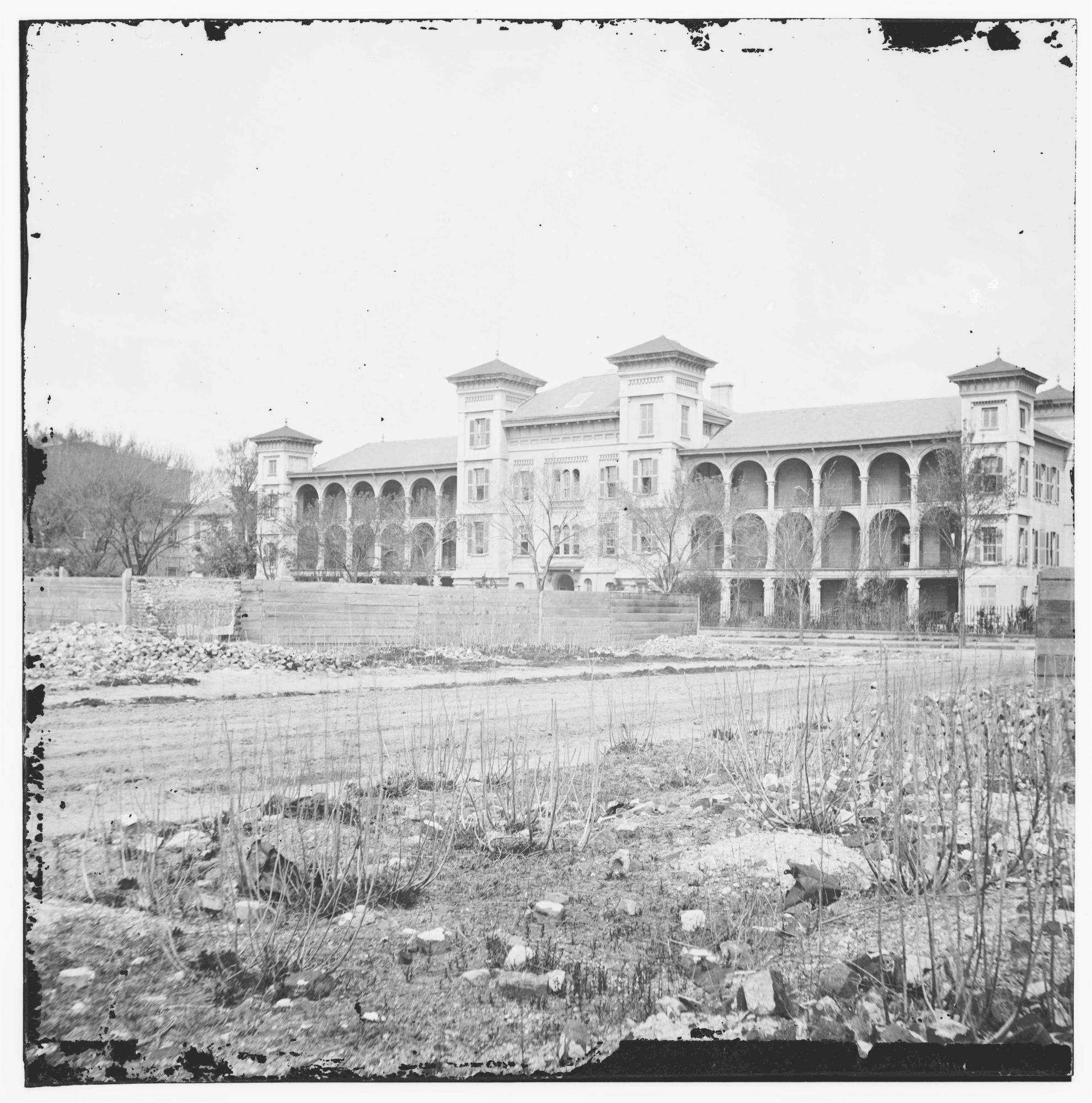

In 1834, the city established the Old Mariners’ Hospital just north of the Medical College and south of the District Jail, along Franklin Street. And finally, in 1852, the Medical Society used a bequest of $30,000 from Colonel Thomas Roper, a former mayor of Charleston who had enlisted to fight for the Patriot cause when he was just 16 years old, to build a hospital to treat the city’s sick and injured “without regard to complexion, religion or nation.” 8 By 1856 Roper Hospital, named for its primary benefactor and located at the corner of Queen and Logan streets on the block’s southwest corner, was admitting patients suffering from the many epidemics that plagued Charleston throughout the 19th century: yellow fever, cholera, typhoid fever and smallpox.

In A Brave Black Regiment, author Luis Emilio quotes from a Charleston Courier newspaper article describing the horrors that occurred at the Roper Hospital during the Civil War: "A chief point of attraction in the city yesterday was the Yankee hospital on Queen Street, where the principal portion of the Federal wounded, negroes and white, have been conveyed. Crowds of men, women and boys congregated in front of the building to speculate on the novel scenes being enacted within, or to catch glimpses through the doorways of the long rows of maimed and groaning beings who lined the floors of the two edifices, but this was all they could see. The operations were performed in the rear of the hospital where half a dozen or more tables were constantly occupied through the day with the mutilated subjects. The wounds generally are of a severe character, owing to the short distance at which they were inflicted, so that amputations were almost the only operations performed. Probably not less than seventy or eighty legs and arms; were taken off yesterday, and more are to follow to-day. The writer saw eleven removed in less than an hour. Yankee blood leaks out by the bucketful....9

All of these public buildings were extensively damaged in the Great Earthquake of 1886, some of them destroyed. The Mariners’ Hospital ceased to serve as a medical facility and instead eventually came to house an orphanage that would cause it to become better associated with the madcap madness of America’s great jazz age of the roaring 1920s. Thanks to the Jenkins Orphanage Band, the sound of music and joy could at times be heard within this historic block. Yet most of the time, not so much so.

Sources

3. Christine Trebellas, Charleston County Jail (Washington, D.C.: Historic American Buildings Survey, 1995), p. 24. Quoted within David C. Scott, Abode of Misery: An Illustrated Compilation of Facts, Secrets and Myths of the Old Charleston District Jail (Charleston, S.C.: Building Arts Press, 2010), p. 33.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. “225 Years of History,” on the the Medical Society of South Carolina website.

7. Jonathan H. Poston for Historic Charleston Foundation, The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City’s Architecture (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), p. 392.

8. “Through the Years, A History of Roper Hospital,” on the Roper St. Francis Healthcare website.

9. Captain Luis F. Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment, The History of the 54th Massachusetts, 1863-1865 (Boston: The Boston Book Company, 2nd Edition, 1894) p. 401. Quoted within David C. Scott, Abode of Misery: An Illustrated Compilation of Facts, Secrets and Myths of the Old Charleston District Jail (Charleston, S.C.: Building Arts Press, 2010), p. 114.