BLIND TIGERS

Charlestonians have always enjoyed a good drink. “The importation of liquors at Charles Town in 1743 staggers the imagination,” noted colonial historian and author Carl Bridenbaugh.

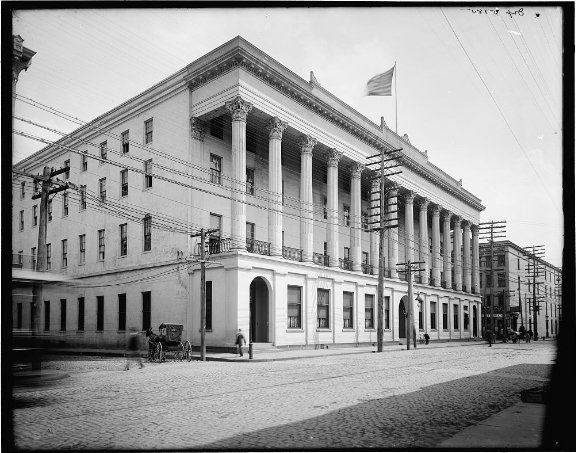

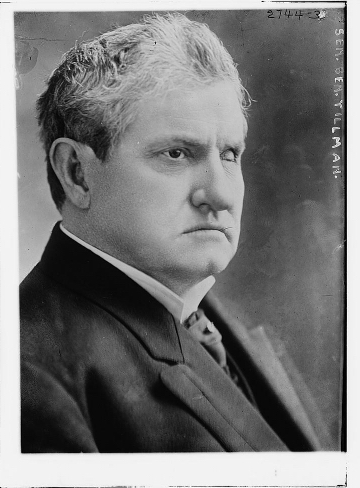

Indeed, if Charlestonians ever needed a good stiff drink, it had to have been in the 19th century’s last few decades. The years following the city’s destruction during the Civil War were packed with natural disasters, chaos, change, bankruptcy and hard times. Not the least of these troubles was the state’s election in 1890 of Gov. “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, a man neither fond of nor popular with the old Charleston aristocracy. Tillman once claimed Charlestonians were “the most idolatrous people in the world,” and he hit the Holy City right where it hurt when he passed the Dispensary Law of 1893. Essentially creating a monopoly, all liquor was sold by the state, no more or no less than one bottle at a time, and drinking on premises was forbidden.

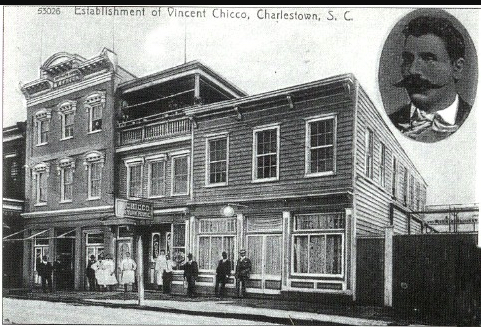

Charlestonians and its law enforcement officials responded at first by simply ignoring the law. Tillman responded by taking over Charleston’s police department and sending down law enforcement raiding parties. Charlestonians’ next move was to create establishments that purported to be exhibition halls, but which were essentially bars illegally selling liquor. They were called Blind Tigers.

Dozens of these exhibition halls opened in Charleston. For a small fee, patrons could enter the hall, have a seat, and wait for a specified period of time for the appearance of a rare, tamed blind tiger. While waiting, the patron was offered a “free” drink, allowable under the law as long as there was no charge for the drink. Of course, it was – and still is – extremely rare that tigers (blind or otherwise) ever make an appearance in Charleston; therefore the patron, if he really wanted to see the tiger, would repay his “admission” fee when his allotted time ran out, take a seat again, and receive his next free drink.

Tillman’s Dispensary Law was repealed in 1907. Of course, national prohibition advocates tried temperance again in 1920, but those laws, too, were met in Charleston with the same enthusiasm – and tactics – of the Dispensary Law. In 1933, the constitutional amendment establishing prohibition in the United States was repealed, eliminating the need for Blind Tigers. Their memory lives on, however, in the names of several local drinking establishments.