Charles Town’s second house of worship, established less than a year after St. Philip’s Anglican Parish Church in 1680, was Protestant, composed of “dissenters” who had not yet sorted themselves out into Lutherans, Congregationalists, Baptists and Presbyterians. They gathered at a meetinghouse that, according to church records dated February 5, 1775, “suffered itself to be called either Presbyterian, Congregational, or Independent: sometimes by one of the names, sometimes by two of them, and at other times by all the three. We do not find that this church is either Presbyterian, Congregational, or Independent, but somewhat distinct and singular from them all.”

Its first building was a small white wooden structure, referred to simply as the White Meeting House. (At the risk of oversimplification, colonial Anglicans and Catholics went to “church,” while Protestants went to “meetings.”) The street leading to the meetinghouse, one of the principal thoroughfares established in the colony’s Grande Modell, was called Meeting House Street, later shortened to Meeting Street.

Some of Charleston’s oldest memorials can be found in this graveyard; the oldest dates to 1685. Taphophiles find a wealth of funerary symbolism here, tracing the evolution of how each generation has visually expressed its evolving attitudes about death and the afterlife. About 500 gravestones remain today, though records suggest that thousands of unidentified souls are also be interred here.

A larger, brick building replaced the wooden meeting-house in 1732. When the city fell to the British in 1780, the meetinghouse was used as a hospital, suffering significant damage. Repairs began within a week after the British withdrew, however, and the congregation continued to grow. By the dawn of the 19th century, it was clear that the church would need to expand.

Charlestonian Robert Mills, acclaimed as America’s first native architect, undertook the design of a new church in 1804 with its iconic circular design. Built in the Pantheon style, it is believed to be the first domed church in America. Though Mills’ design did not include a steeple, by 1838 German architect Charles Reichardt had added one. The renowned antebellum architectural team of Edward Jones and Francis Lee updated the large portico, which projected dominantly over the sidewalk, from Tuscan to Corinthian style columns in 1852-1853.

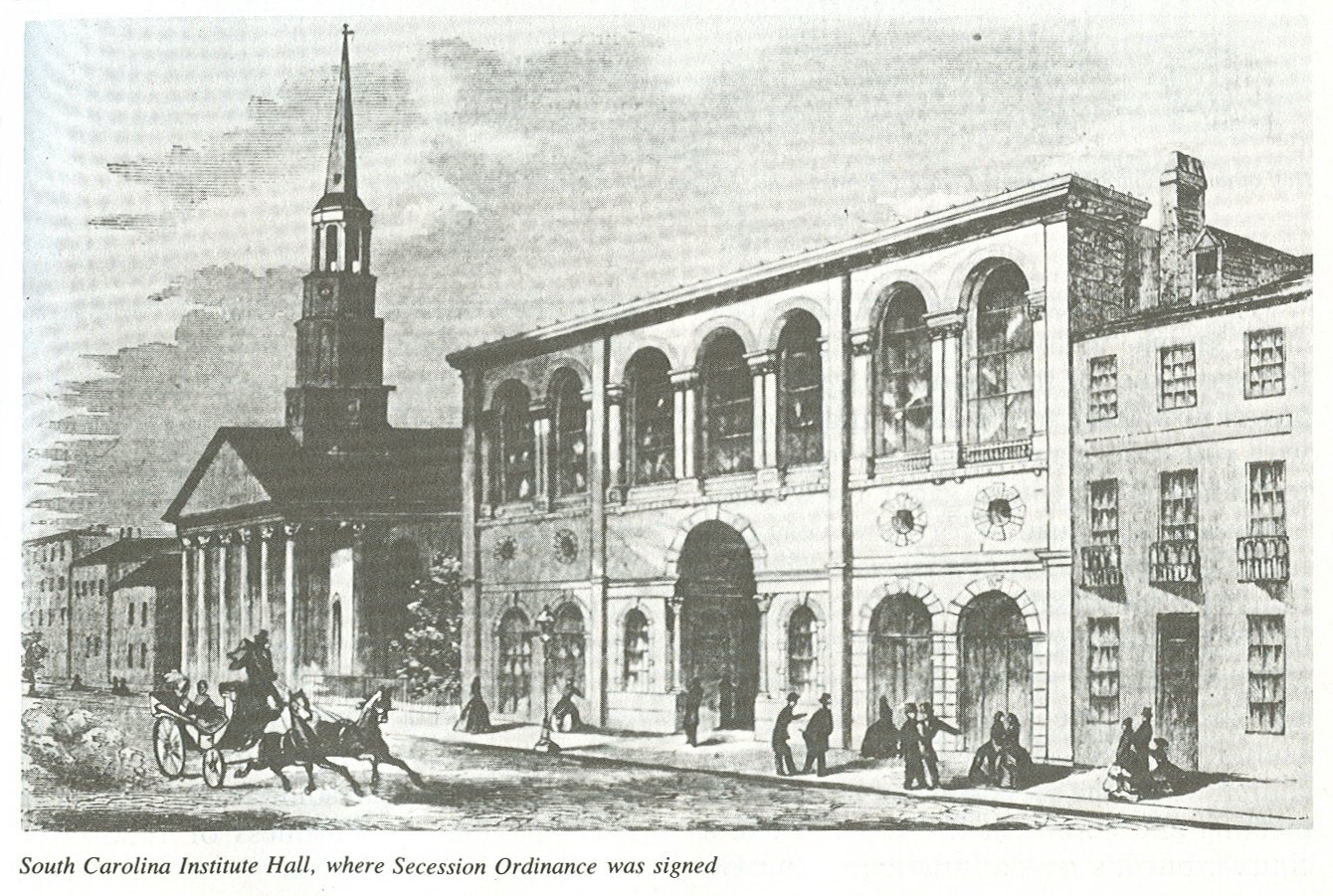

The Great Fire of 1861 destroyed the church as well as its neighbor, S.C. Institute Hall; the burned-out structure also suffered from Federal shelling and vandalism during the next four years of Civil War. Though its exterior walls stood, it would be years before there would be funding to undertake major repairs. Fate, however, was not yet done with the church: even as repairs began, the remaining walls crumbled in the Great Earthquake of 1886. Salvaging bricks from Mills’ structure, New York architects Stevenson and Green rebuilt the church in 1890-1892 in the Romanesque Revival style.