EVACUATION OF FORT MOULTRIE

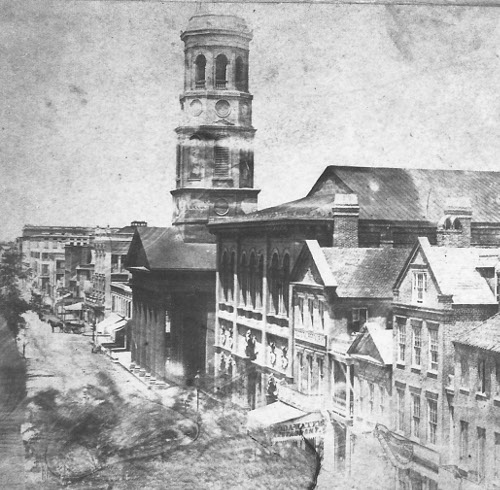

Rarely do momentous things happen during Christmas week, when everyone is at home with their family, gathered ‘round the fireplace (or more likely the television), eating delicious things. But that wasn’t the case in 1860. That Christmas, things were tense in Charleston, everyone’s nerves on edge.

Five days earlier, South Carolina had seceded from the Union, declaring itself the new “independent republic of South Carolina.” Well before that November’s Presidential election, the state’s leadership had said it would withdraw if Abraham Lincoln won, and they meant it.

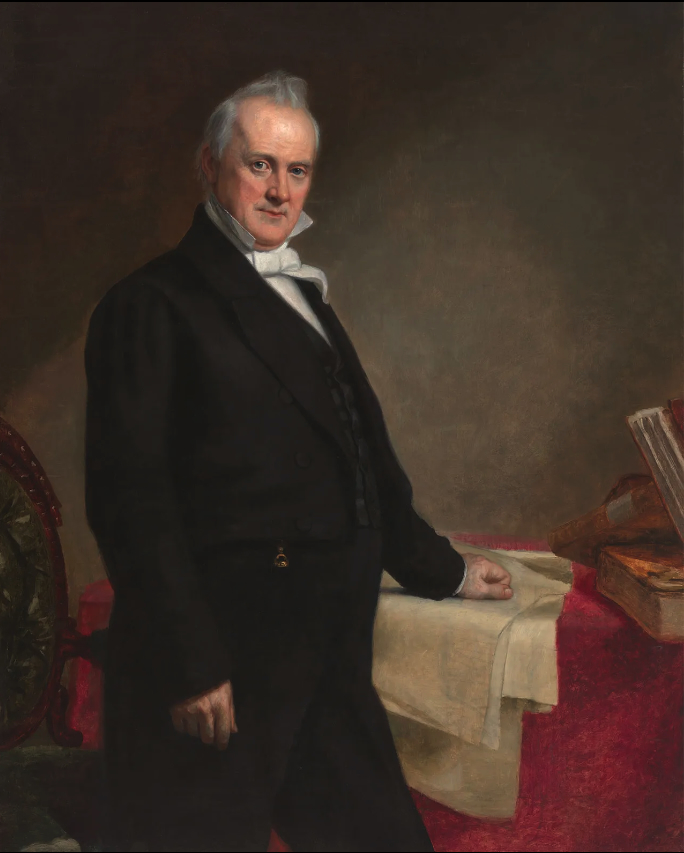

Knowing secession was imminent, the state’s congressional delegation and others met with President James Buchanan – Lincoln would not take office until March – urging him to surrender federal properties once secession was announced, particularly military assets that included the Arsenal (today part of MUSC’s campus) and the city’s four forts.

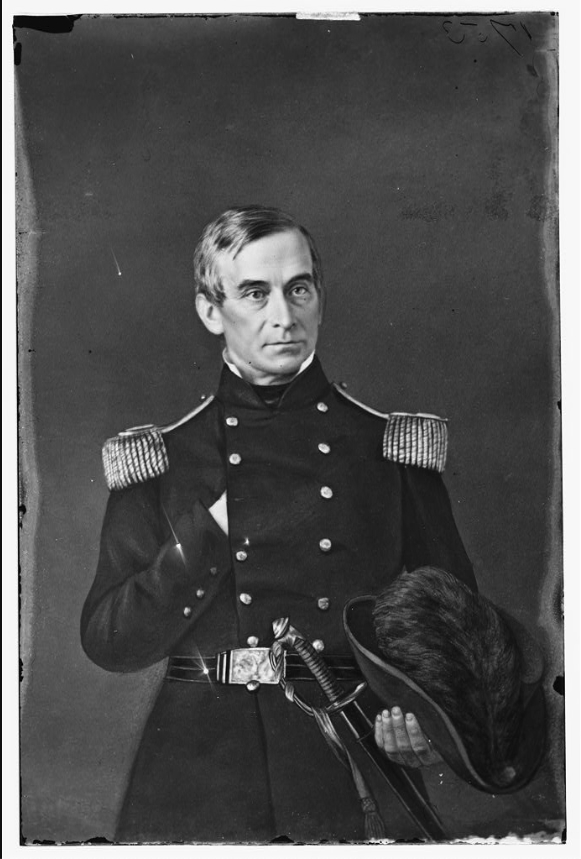

That Christmas, Castle Pinckney was primarily being used for storage, Fort Johnson was in extreme disrepair, and Fort Sumter’s interior was under construction. Only Fort Moultrie served as an active military fortress, garrisoned by about 85 men under the command of Maj. Robert Anderson, a former artillery professor at West Point Military Academy and son of Major Richard Anderson, who had defended Fort Moultrie during the American Revolution.

(As an aside: one of Anderson’s students had been a promising young man named Pierre G.T. Beauregard, and the two developed a lasting respect for one another. More on that in a future column.)

Buchanan did not want the war to begin during his final months in office, yet he was unwilling to surrender the forts. Trying to find a way out of this sticky situation, he met with the state’s congressional delegation on Dec. 8 and 10, offering verbal assurances that he did not intend to reinforce the forts until a peaceful transfer of properties could be negotiated. In return the Carolinians promised they would not attack the forts before then.

While Buchanan said he would make the delegation aware of any changes to this policy, he refused to put the agreement in writing, leaving it dangerously open to interpretation.

Being unaware of any understanding to maintain the status quo until transfer negotiations were finalized, Anderson contacted his superiors in Washington expressing concerns about his men’s safety at Fort Moultrie – for having been built as a coastal defense, Moultrie’s ordnance faced seaward. Its rear was not defendable from a land attack.

Buchanan, through his Secretary of War J.B. Floyd, responded that though Anderson should not provoke the Carolinians, he was to retain possession of the forts. If he and his men were attacked, however, they should do whatever necessary to defend themselves, and any attempt by the South Carolina militia to take the forts should be considered an “act of hostility.” Finally, they gave Anderson the option to place his men in whichever fort he felt was most defendable.

That Christmas, Anderson made his decision, one that would redirect the course of American history.

Given the growing tensions between Charlestonians and his troops, Anderson feared a hostile attack, later writing “I was certain that if attacked my men must have been sacrificed, and the command of the harbor lost.” That evening, under cover of darkness, Anderson and his men quietly packed up what supplies they could and secretly boarded boats for Fort Sumter, which Anderson felt – being surrounded by water – was safer.

Capt. Abner Doubleday, who today is generally – though probably incorrectly – credited with inventing the game of baseball, later wrote: “Anderson approached me as I advanced, and said quietly, ‘I have determined to evacuate this post immediately, for the purpose of occupying Fort Sumter; I can only allow you twenty minutes to form your company and be in readiness to start.’ I was surprised at this announcement, and realized the gravity of the situation at a glance.”

Charlestonians were livid, feeling that Anderson’s move violated their agreement with Buchanan to maintain the status quo. Many felt it was a just excuse to begin the war.

Despite their earlier orders to Anderson to hold whichever fort the major deemed safest, Buchanan and Floyd seemed surprised by news of the evacuation and called a cabinet meeting on Dec. 27, the same day the state’s militia easily seized Castle Pinckney, Fort Johnson, and the abandoned Fort Moultrie.

On Dec. 28, Buchanan confirmed his refusal to surrender Fort Sumter. Everyone held their breath, waiting for what would come next.

It had, indeed, been a very eventful Christmas week.