CASTLE PINCKNEY

Though most history books teach that the Civil War began April 12, 1861, with the firing of the first shot at Fort Sumter, perhaps the first overt act of war actually occurred Dec. 27, 1860, when Charleston militia ousted a small group of civilian laborers and two U.S. Army soldiers garrisoned at Castle Pinckney, making it the first Federal military installation seized by what was then the Republic of South Carolina, soon to evolve into the Conferate Army as other Southern states joined in. Rapid advancements in early 19th century weaponry caused Castle Pinckney to become obsolete within a decade of its completion c. 1810, dooming it to become little more than a footnote in the grander stories of its neighboring forts, Moultrie and Sumter. Still, as the first Federal installation to fall in the American Civil War, Castle Pinckney has an important place in history, if not in the popular retelling of it.

During his 1791 visit to Charleston, George Washington recognized the strategic value of this spit of land where the Cooper River transitions into Charleston Harbor. He ordered a fort be built there to defend against a naval attack from France that seemed imminent, yet never happened.

A log structure named for Washington’s local host, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the first fort built here was destroyed by a hurricane just months after its completion in 1804. A second, made of bricks and mortar, was completed in 1810 in anticipation of the War of 1812. Its innovative design featured elliptical fortresses that housed cannon inside. Built to house 200 men, the fort resembled a medieval castle, thus its popular nickname.

Charleston saw no action in 1812, however, and within a decade new cannon with increased firing ranges made the fort, located so close to High Battery, obsolete. As plans for Fort Sumter began in 1826, Castle Pinckney was abandoned and began its long fall into disrepair. It was briefly re-garrisoned when South Carolina threatened secession during the Nullification Crisis of 1832, but again crisis was averted and it became an arsenal for storage.

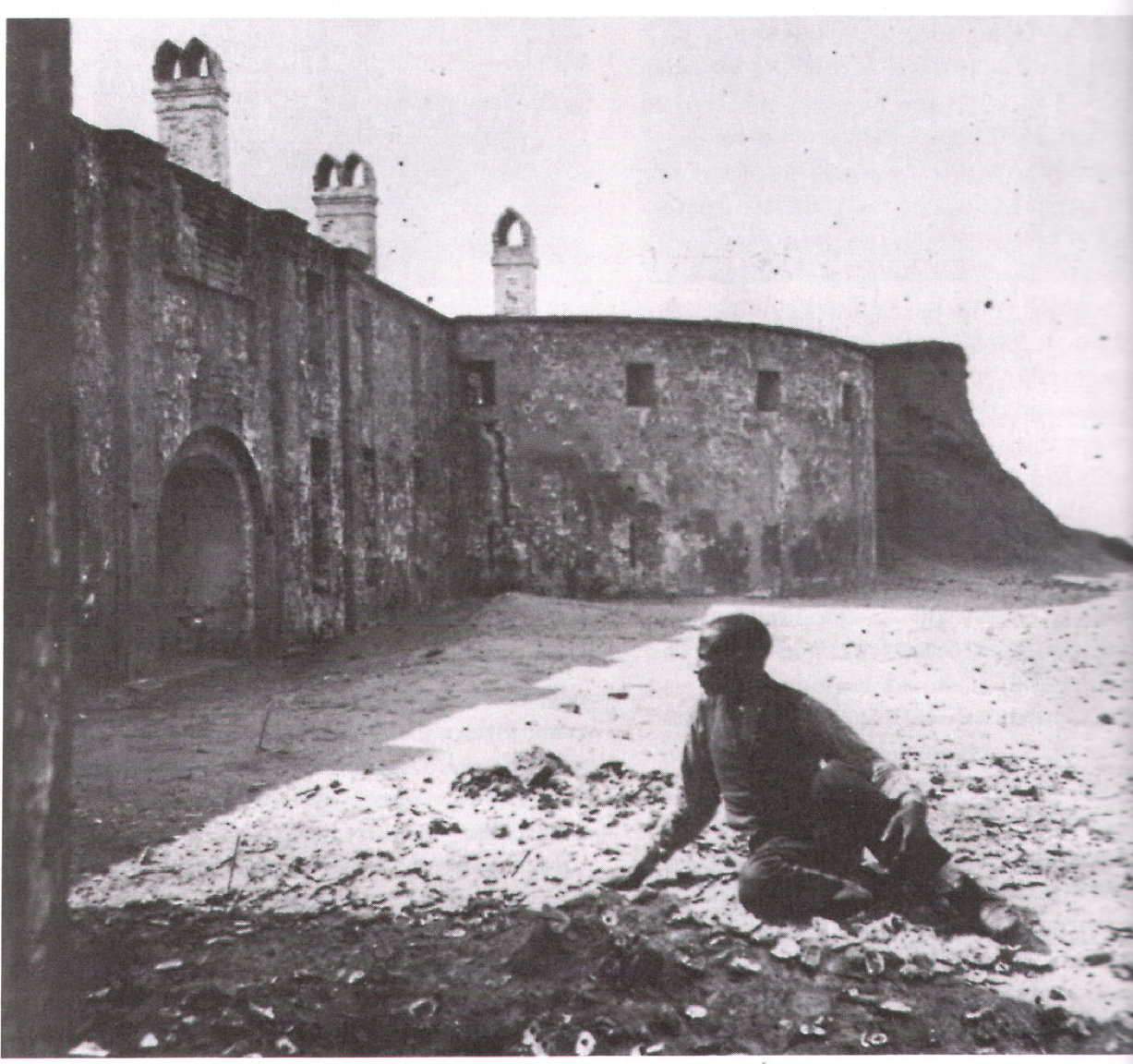

In September 1861, it was repurposed as a POW camp for Union prisoners. According to the Charleston Mercury, they included captives “who had evinced the most insolent and insubordinate disposition.” Nevertheless, life at Castle Pinckney never yielded the horror stories of other camps such as that at the Washington Race Course. Perhaps because it was an island, prisoners were allowed to wander freely during the day, returning to their cells at night. Photographs suggest that prisoners and their captors shared a sense of humor and civility.

The number of prisoners soon outgrew the facility and they were moved to the City Jail. After the Jail was damaged in the Great Fire of 1861, however, 300 prisoners were crowded into Castle Pinckney before being dispersed among other prisons. Federal troops reclaimed the fort Feb. 18, 1865.

In 1897, some suggested transforming the castle into a veterans’ retirement home. Nevertheless, the site served only as a lighthouse until 1917, when even that was abandoned. In 1924, President Coolidge designated Castle Pinckney a National Monument, an act repealed by Congress in 1956 due to lack of interest and funding. It changed hands several times over the next five decades and was named to the National Register of Historic Sites in 1970. The Sons of Confederate Veterans Fort Sumter Camp No. 1269 acquired it in 2011 for $10 Confederate. It seemed an appropriate trade.

Only a portion of its brick foundation and a canon remain. No plans have been made for its future.

The location of Castle Pinckney in Charleston Harbor can be seen in this map showing Confederate defenses of Charleston. Castle Pinckney is at right, top third of image. (Photo: Library of Congress)

An artist's rendering of the fort at its peak. (Image: Wikimedia)

The rounded battlements of the fort can be seen in this image taken by an unknown photographer in 1861. (Photo: from the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, public domain, Wikimedia)

Because it was located on an island in Charleston Harbor, the Federal prison on Castle Pinckney allowed its inmates a considerable degree of freedom during the day. This image of the fort's interior, taken in August of 1861, is one of several that imply that the inmates and their guards got along quite amiably, unlike other camps such as that at the Washington Race Course. (Image: The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume One, The Opening Battles. The Review of Reviews Co., New York. 1911. p. 164. Public domain. Wikimedia.