GREAT FIRE OF 1861

Few dates hold as prominent a place in Charleston’s story as Dec. 11, a date that in 1861 changed our city forever as the largest fire in its history obliterated nearly a third of its structures.

With buildings nestled closely together within its defensive walls, Charleston had seen its share of fires: in 1698, 1740, 1788, 1796 and three in the 1830s. They were each, in their own way, catastrophic in what they destroyed. Yet nothing had prepared Charlestonians for the evening of Dec. 11, 1861.

Tensions in the city that day were palpable. It had been almost a year since South Carolina seceded from the United States, and the first shots of the Civil War had been fired in Charleston Harbor earlier that year. Some foolishly thought South Carolina’s victory at Fort Sumter would be the extent of the war. But of course not.

While battles raged in Virginia, Missouri, Kentucky and Florida, little in Charleston had happened since Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard sent the defeated Federal defenders of Fort Sumter safely home to New York. Everyone was holding their breath, anxiously waiting for what would come next.

Accounts describe Dec. 11 as a typically mild winter’s day. Yet as evening fell, an approaching cold front brought brisk winds from the northeast, winds that around 8 p.m. stoked a small fire at the corner of Hasell and East Bay streets, near where the Harris Teeter grocery store stands today.

Accounts conflict about how the fire started. Diarist Emma Holmes, from her grand residence at 19 East Battery, and Fire Chief Moses Henry Nathan, whose departmental records were rediscovered about a decade ago, both claimed Union soldiers strategically set the fire on the city’s northeast corner. Other said Confederates set the fire to blame Unionists and inflame passions for a military confrontation.

Perhaps it began when the evening’s increasingly strong winds accidentally caused a cook fire or embers from a brazier to spread. We’ll never know.

By midnight, the blaze had pushed south along the wharves to the City Market, where it engulfed the mansion built by Charles and Eliza Lucas Pinckney in 1746, also the residence of Charleston’s last royal governors. Their elderly granddaughter, Miss Harriet Pinckney, barely escaped before her family home was destroyed.

Burning through the Market, a southerly shift in the winds drove the fire down Meeting Street, leaving both the Circular Church and S.C. Institute Hall, where the Ordinance of Secession had been signed, in ashes and rubble.

Gen. Robert E. Lee, in town to inspect the city’s defenses, stood atop the Mills House hotel watching the oncoming flames until they reached Institute Hall, at which point he sought refuge at the Edmondston-Alston House on East Battery. Everyone else had already evacuated the Mills House, sources said, except for some of the enslaved staff, who used the hotel’s innovative running water spigots to wave soaked bed linens from its windows to stave off the flames.

Some doubt the staff’s gallant efforts could have been enough to save the hotel. If so, then perhaps it was their prayers that miraculously shifted the winds again in a westerly direction at Queen Street, scorching, but not burning, the Mills House.

Firefighters blew up 14 houses along Queen Street in an effort to arrest the flames before they reached the Catholic Orphanage and District Jail, where hundreds of Union POWs were imprisoned. As their Confederate guards left to help fight the fire, prisoners were densely packed into the jail’s upper floors. With the fire so large and so close, prisoners who were small enough made their way through the windows’ bars and jumped for their lives.

Shifting again in a southerly direction at Logan Street, the fire bypassed the jail, racing down Logan and Legare streets to Broad Street. Sources say that surprisingly, none of the escaped Union prisoners fled after their desperate jumps from the jail’s upper windows, instead waiting in an orderly fashion for their guards to return the next morning.

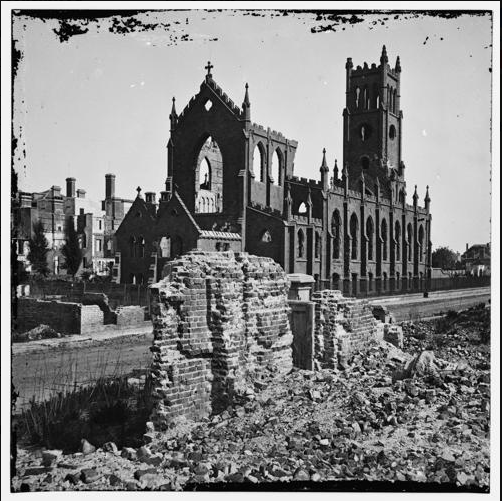

Nearly every building on Broad Street, from King Street to what was then the city’s western edge at Rutledge Avenue, lay in the fire’s path. The recently completed Cathedral of St. John and St. Finbar was left no more than a shell, as was its neighbor, St. Andrew’s Hall, where the Ordinance of Secession had been drawn up the year before.

When the fire reached the Ashley River, it continued south, destroying the western end of Tradd Street before burning itself out near the corner of South Battery and Legare Street around noon Dec. 12. It had destroyed 540 acres through the heart of the city, an estimated 500 residences, five churches, at least two civic buildings and hundreds of businesses. Thousands were left homeless.

When people see photographs of the ruined city taken in 1865, most assume the destruction was the result of the war. Yet most of the devastation seen therein was the result of the 1861 fire.

When Sherman’s troops left Savannah after Christmas 1864, most thought he would march on to Charleston. Instead, he headed north to destroy Columbia, knowing there was little left to burn in Charleston.

Fire Chief Nathan noted that in a way, the fire had a small silver lining. With so many buildings destroyed, many residents left Charleston long before Federal troops began shelling a city that was already in ruins.

Sources and for more information:

Image by David Quick, Post and Courier