KRESS LUNCH COUNTER SIT-IN

A retail icon in cities across America from 1896 until the 1980s, S.H. Kress & Co. stores were renowned for their architectural excellence. Among Charleston’s most notable Art Deco buildings, its store at 281 King St., c. 1931, features exotic Mayan Revival details in butterscotch terra cotta with decorative festoons and geometric motifs.

Kress stores appealed to urban as well as small town and rural customers. An article in an old Sandlapper Magazine opined that Kress was more than just a place to buy toiletries and sundries. It was the kind of place where friends could meet for a grilled cheese sandwich at its lunch counter.

Unless you were Black.

Kress’s policy of excluding African Americans from their lunch counters changed the trajectory of the Civil Rights discussion in Charleston. Though local pastors and NAACP leaders talked about civil rights before 1960, the national movement was something most Charlestonians watched passively from the sidelines.

On Feb. 1, 1960, four Black college students staged the first peaceful sit-in at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., spurring similar collegiate protests across the South. Charleston, however, had no Black college students; neither the College of Charleston nor The Citadel accepted African Americans at that time.

Instead, 24 students at Burke High School began quietly meeting with local leaders, learning tactics of successful non-violent demonstrations. On the morning of April 1, a teachers’ workday that circumvented any charges of truancy, 16 Black boys and eight girls from Burke walked down King Street in suits and dresses prepared to ramp up the Civil Right discussion in Charleston.

These students were aware of the risks they were taking, not only for the possibility of violence and arrest, but also for retaliation against their parents who might be fired from their jobs because of their actions. Still, they were committed to their cause.

They had planned the sit-in to be at the Woolworth’s counter, also on King Street, but having gotten word of the planned protest, Woolworth’s stationed police outside its store and filled its seats with White customers before the students arrived.

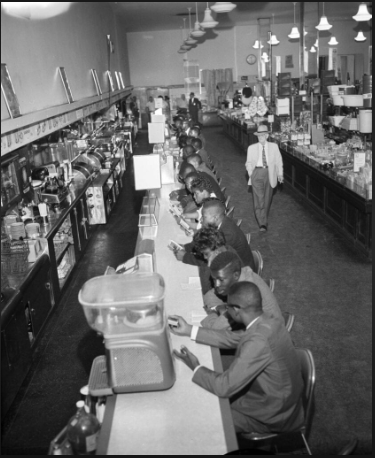

Undaunted, the students continued down the block to Kress’s lunch counter where they sat and politely asked to be served. As expected, they were told to leave. They didn’t.

Kress’ staff then removed unoccupied stools to keep the protest from growing. When the students still refused to leave, employees scrubbed the counter with an ammonia cleaner that gave off toxic, nauseating fumes.

Nevertheless, for the next five hours, the students remained seated, behaved respectfully, and quietly hummed, prayed and recited Bible passages. Shortly before 5 p.m., someone called in a bomb threat, and police called for an evacuation of the building. The students remained seated in an orderly, yet determined, manner.

They were arrested without incident and charged with trespassing. Bail was set at $10 each and paid by Charleston’s NAACP chapter president, J. Arthur Brown, whose daughter was among the protesters. All charges were later dropped.

The Kress sit-in was the first overt public action of the Civil Rights movement in Charleston. The teenagers’ bravery inspired adults to get involved, setting the stage for other non-violent protests in Charleston throughout the 1960s.

The Civil Rights Act passed in 1964. Kress closed in 1981, though Charleston’s store continued operating as McCrory’s before closing for good in 1992. Many businesses have occupied 821 King St. since then, including clothing stores, a rug gallery, law offices, Williams Sonoma, and most recently H&M home goods.

Its interior has been heavily renovated, and the lunch counter removed. The Preservation Society of Charleston erected a historical marker there in 2013, interpreting the importance of the site to the Civil Rights movement in Charleston.