SEA ISLAND COTTON

This essay is adapted from Lost Charleston.

Learn more on our Sea Islands Tour.

Few images romanticize Charleston quite like fields of snowy white cotton, a cliché popularized in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. Though Charleston’s great colonial fortunes had been founded on rice and indigo, the latter’s value dropped sharply after the American Revolution when the British stopped paying import bounties. Charlestonians needed a replacement crop. With the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, the timing for the new crop’s introduction was perfect.

Charlestonians didn’t grow just any cotton. They grew Sea Island cotton and that was an important distinction. The species Gossypium barbadense could be grown only within 15 miles of the coastline between Georgetown, S.C., and St. Mary’s River in Georgia. Standing 6 feet tall, it produced a silky fiber about two inches long that was as strong as it was soft. Research historians suggest a pound of Sea Island cotton could be stretched as far as 160 miles without breaking.

Sea Island was unquestionably the most valued cotton of the 19th century, commanding a higher price than any other in the world and as much as ten times that of inland varieties. It was used to produce the finest European goods, including Queen Victoria’s handkerchiefs and undergarments for the French and English nobility. It soon joined rice as the most important crop of 19th century Charleston. In 1855 it sold for 30 cents a pound, making each bale worth about $100 (equivalent to $3,500 today).

Because demand was so high, Lowcountry planters emphasized quality in addition to quantity. Neighboring plantations competed to grow the silkiest and strongest cotton, painstakingly selecting the best seeds each year to plant the next crop, guarding them carefully, and handing them down through generations. Each bale was proudly stamped with the plantation’s brand.

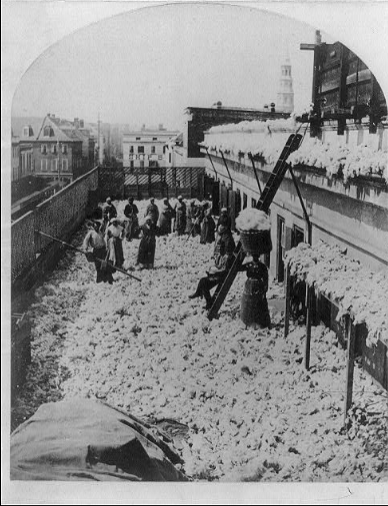

Like rice, the profitable production of Sea Island cotton was dependent upon an enslaved workforce. Its cultivation and harvesting required intensive labor with a growing season that lasted 250 days. After being cultivated and picked by hand, it required a series of tasks to prepare for market including drying, ginning and sorting for quality. Each 300-pound bag required the equivalent of 400 hours of enslaved labor to prepare. Thus emancipation was one of several reasons for the crop’s decline.

A disease known as cotton wilt also diminished the quantity and quality of the crop in the 1870s. Inland cotton, with its shorter fibers, became easier and cheaper to gin. Yet it was a ravenous little bug known as the boll weevil that ended the reign of “King Cotton” beginning in the late 1890s. By 1930, the pest had nearly eradicated Gossypium barbadense.

For nearly 85 years, it was believed that the last seeds had been lost or destroyed, making the species extinct. Recently, however, seeds from Bleak Hall Plantation were discovered at a Texas repository. Volunteers, through a partnership with Charleston County Parks and Recreation, planted an experimental plot of 25 seeds at McLeod Plantation in 2017, hoping the crop might be regenerated. The experiment met with limited success and has been discontinued. Even had it succeeded, however, there’s little hope it could ever be commercially viable again, botanist Dr. Richard Porcher said in an interview with Charleston’s City Paper, adding “Sea Island cotton is now history.”