BATTERY WAGNER

The week of July 10-18, 1863, was among some of the bloodiest days in Charleston’s history: the Civil War battles of Battery Wagner, fought on the southern tip of Morris Island. This battery was a vital target for the Union Army, for the key to taking Charleston was to control the harbor, and the key to getting through the harbor was to occupy Fort Sumter, strategically located in its middle.

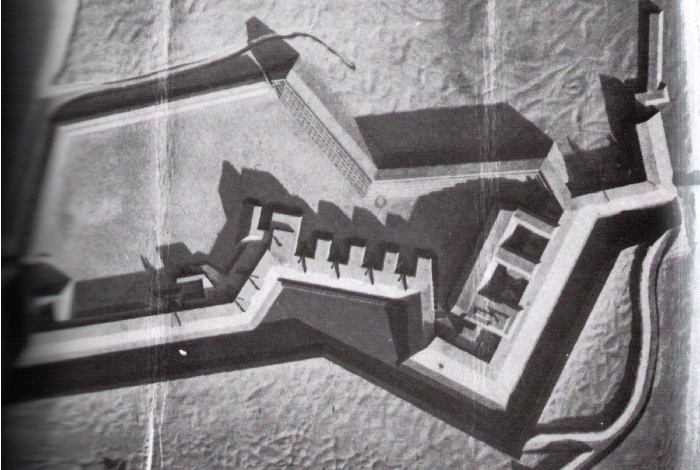

Yet to take Fort Sumter, Union troops would need to take Battery Gregg, virtually a stone’s throw away on Morris Island – and to take Battery Gregg, one had to first take Battery Wagner, which lay about 1,000 yards to its south. This site was selected because it was the narrowest part of the island, somewhere between 25 and 60 feet wide, depending on tides.

On July 10, from their base on Folly Beach, U.S. forces attacked Confederate positions in the southernmost part of Morris island, pushing as far north as Battery Wagner before they had to turn back. Though inconclusive, this attack marked the beginning of the 587-day Siege of Charleston, the longest siege operation of the war.

The next day, July 11, 1,200 Union soldiers ran at the battery head on. Though outnumbered, conditions were in the Confederates’ favor, and they turned back the Union attack with Confederate forces losing only 12 soldiers while 339 Union soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or missing.

Over the next week, Federal ships and ground forces continued to bombard both Wagner and Sumter, and a second attacked was planned for July 18. This second battle is better remembered than most, thanks to the 1989 movie “Glory,” which recounts the story of how the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, among America’s first African American regiments, fiercely led the charge against the Confederate battery.

Again, though 5,000 Union soldiers went up against about 1,600 Confederates, the engagement was again disastrous for the Federal troops, who charged the battery running along a narrow strip of beach with marshes on one side and the Atlantic on the other.

Although exact numbers vary and have never been definitively ascertained, about 36 Confederates were killed and 190 wounded that day. Loses were much greater for the Union, with 246 dead, 880 wounded, and 389 missing or captured. Confederate Gen. Johnson Hagood later reported burying around 800 bodies in mass graves behind the beach.

Despite these losses, however, the courage and commitment shown by the all-Black regiment demonstrated to critics in both the North and the South, that African Americans had the character and competencies to be strong soldiers.

Though suffering two defeats, the U.S. forces continued to bombard Battery Wagner until Confederate forces finally evacuated the position and that of Battery Gregg on Sept. 5.

An even deeper history, however, can be found in the stories of the people who were there -- for it’s those stories, more so than the facts, that give history context and teach us the lessons to be learned. One of those stories is that of Clara Barton, who was motivated in part by her experiences at Battery Wagner to found the American Red Cross.

A Union army nurse, Barton found herself in the thick of Fort Wagner’s second assault. She later wrote about her experience on Morris Island, as her wounded Black patients looked up “ … in utter silence, … and whenever I met one who was giving his life out with his blood, I could not forbear hastening to tell him lest he die in ignorance of the truth, that he was the soldier of Freedom he had sought to be, and that the world as well as Heaven would so record it.”

Later, she wrote “We have captured one fort - Gregg - and one charnel house - Wagner - and we have built one cemetery, Morris Island. The thousand little sand-hills that in the pale moonlight are a thousand headstones, and the restless ocean waves that roll and breakup on the whitened beach sing an eternal requiem to the toll-worn gallant dead who sleep beside."

A few years after the war was over, Union Gen. Quincy Gillmore, an engineer, led an effort to deepen Charleston Harbor’s shipping channel by building jetties. The resulting shift in coastal dynamics caused Morris Island to begin eroding. Over the next two decades, all remnants of the bloody attacks on Battery Wagner slowly sank beneath the ocean’s surface, including the “thousand little sand-hills” that held remains of the dead.

Though the battery itself remains submerged, in 2008 a group including the American Battlefield Trust purchased 118 acres of high ground and marsh adjacent to the fort’s site from a developer who had considered building a resort community there. These preservation efforts, and the stories the survivors left us, provide us with the opportunity to understand and appreciate the deeper, more personal history beyond the statistics.