THE LOST VILLAGE OF CHILDSBURY

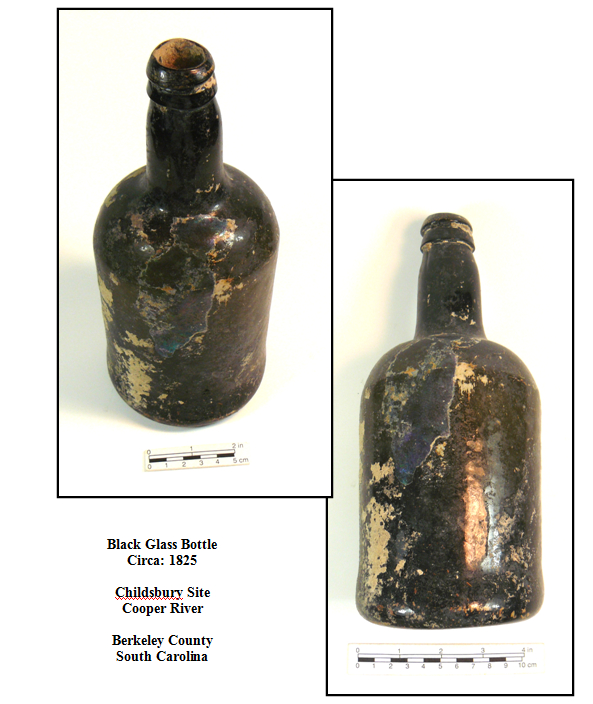

Once the dream of a late 17th century visionary, few traces of the lost village of Childsbury remain, though occasionally archaeologists and SCUBA divers discover new artifacts that recall the brief existence of James Child’s great civic endeavor.

Little information about Child’s early life has survived, though Keith Gourdin, writing for the Berkeley Independent in 2023, says that Child “had been a victim of the tyranny of Lord Jeffreys” in England and imprisoned for not paying taxes. Afterward, he sold his property below market value and left with his wife and eight children to begin a new life in Charles Town.

In 1698 Child was granted 1,200 acres known as Strawberry, overlooking the western branch of the Cooper River near present-day Cordesville. An act of the colonial assembly in 1705 allowed Child to establish a ferry on the branch’s eastern bank where it became too shallow for large, ocean-going ships to continue upriver.

For the next 225 years, Strawberry Ferry played a vital role transporting people and agricultural products from the upper reaches of the Cooper River on the colony's frontier to Bluff Plantation (near what today we know as Cypress Gardens), where travelers continued along the “Broad Path,” roughly today’s old Highway 52, on to Charles Town.

Yet Child had bigger ambitions. Over the next several years, he added 1,500 acres to his property and began selling lots for Charleston’s first planned inland satellite colony, which he named after himself.

Childsbury featured 182 lots laid out in 24 squares with straight, gridded streets that were 66 feet wide, plenty of room for carriages to safely pass one another. Plans included a racetrack, general store, and tavern with an inn for ferry passengers. Lots were set aside for a tanner, blacksmith, butcher, shoemaker, carpenter, and other artisans.

In his 1718 will, Child donated property for a chapel and a market in the middle of town. In 1723, the Commons House of Assembly established market days in the village on Tuesdays and Saturdays, along with annual fairs in May and October.

Child also left lot number 16 for trustees to build a free school for White children living along the Cooper River, provided their families sent along firewood or paid the schoolmaster two shillings and sixpence annually.

The school was completed by 1733 and a Huguenot couple hired as teachers according to the assembly’s specifications: “That the Master shall be of the religion of the Church of England and conform to the same, and shall be capable to teach the learned languages - that is to say, the Latine and Greek tongues - and also the useful part of the Mathematicks, and to catechize and instruct the youth in the principles of the Christian religion as professed in the Church of England.”

Child also bequeathed 600 acres to create a communal farm and pasture, where each lot owner could graze two cows. Finally, he left 100 acres on a high bluff to build a fort to protect villagers from unfriendly natives, marauding Spaniards from St. Augustine, and pirates.

By the late 1730s, Charles Town’s economic base had shifted from trade with the natives to rice cultivation. Childsbury became surrounded by plantations that had their own docks and transportation, as well as skilled enslaved laborers which supplanted the need for Childsbury’s artisans.

Small farmers and tradesmen could not compete with these sprawling estates. By the 1740s, Childsbury began being absorbed into nearby plantations. The ferry’s principal function was reduced to transporting passengers to church or neighboring plantations.

The village tavern remained active for a while as a stop along the way to Charles Town, as did the semiannual market fairs. The track continued hosting horse races through the mid-1700s; the Strawberry Jockey Club disbanded in 1822, after which the racecourse was ploughed under to become a corn field.

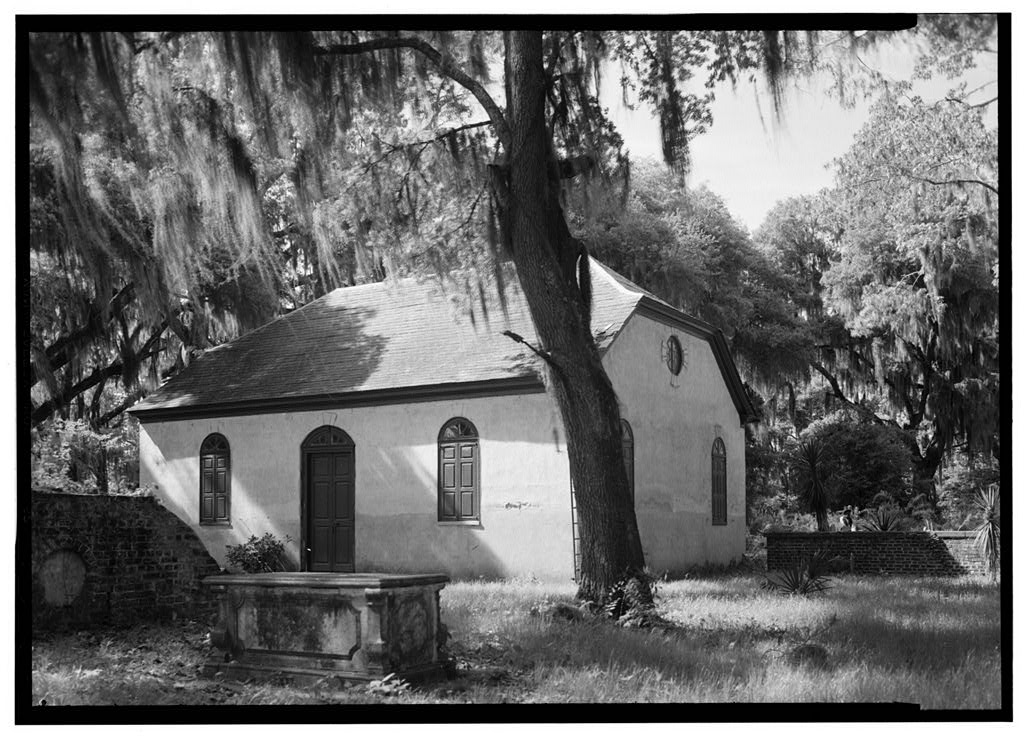

Though Strawberry Chapel continued serving a small congregation into the 19th century (and still does today on a limited basis), by the time of the American Revolution, Childsbury no longer existed. By the 1920s, with the advent of cars, even the ferry ceased operations.

The only visible remains of Childsbury today is Strawberry Chapel, which is privately owned. Most of the rest has become a forested state heritage preserve, rarely visited except by ardent anglers who enjoy quiet afternoons dropping a line from its dock.

John Child's plan for his village as drawn by 1707.