TWO WEEKS LEADING UP TO THE FIRING ON FORT SUMTER

A version of this essay ran in the Post and Courier's Do You Know Your Lowcountry columns on March 31 and April 7.

As March slipped into April 1861, America stood at a crossroads. About the only thing the North and South agreed on was that neither wanted to start the American Civil War.

If President Abraham Lincoln surrendered Fort Sumter, as South Carolina demanded, he would be acknowledging the end of the Union which he said he would never do in his inaugural address.

Yet according to historian Robert Rosen, author of A Brief History of Charleston, if Confederate President Jefferson Davis and S.C. Gov. Francis Pickens allowed Federal troops to remain at Fort Sumter, the Confederate government would appear so weak it had to allow an enemy force to maintain a military presence in one of its most important ports. Plus, if the South initiated the war, thousands of Northerners who were noncommittal about secession would rally to Lincoln’s support.

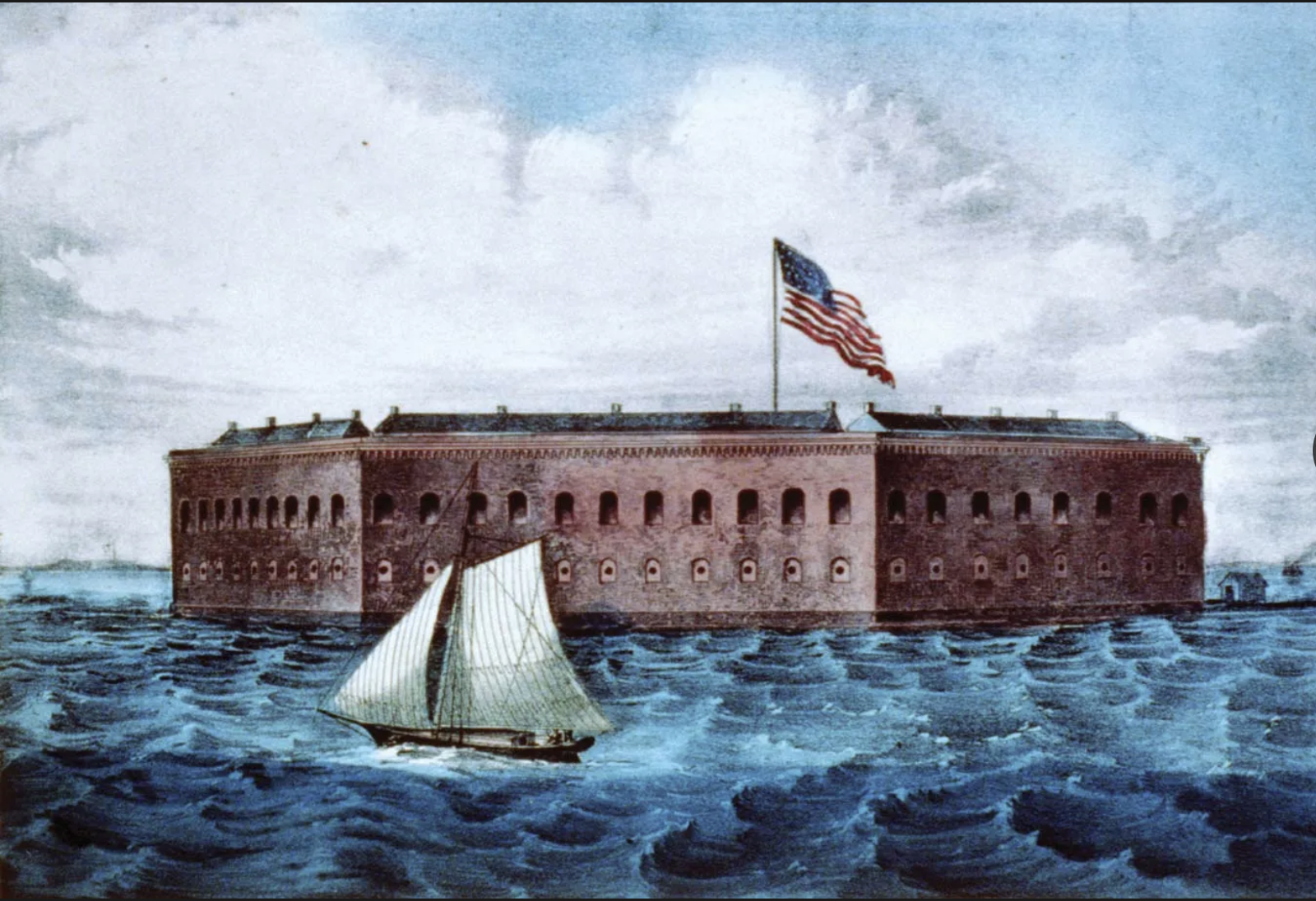

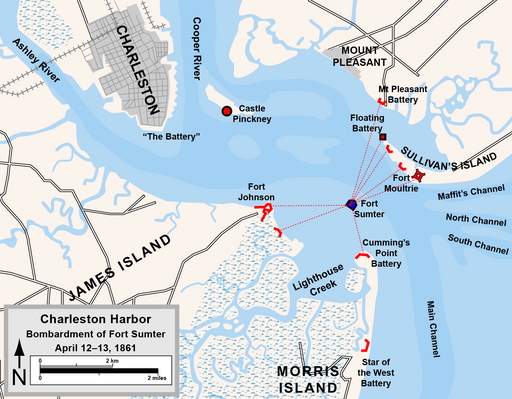

The 85 or so Federal soldiers at Fort Sumter, under command of U.S. Maj. Robert Anderson, were in an indefensible position against 6,000 Confederate troops who surrounded them. They knew Anderson couldn’t hold out much longer, as he was running out of food and supplies.

Against the advice of his Cabinet, Lincoln decided to resupply Anderson. If the Confederates fired on ships sailing under the U.S. flag, he reasoned, the North would be justified in defending themselves, and the South would be held responsible for initiating the war.

Here’s how the two weeks leading up to the firing on Fort Sumter unfolded.

April 1

After meeting with Secretary of State William Seward, Army Capt. Montgomery Meigs, and Navy Lt. David Porter, Lincoln ordered the commandant of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Capt. Andrew Foote to prepare the warship Powhatan for an undisclosed mission and replace its captain, Samuel Mercer, with Lt. David Porter. To maintain absolute secrecy, the order said under no circumstances was the U.S. Navy Department to be informed.

Meanwhile, Mercer had conflicting orders from Navy Secretary Gideon Welles for the Powhatan to relieve Fort Pickens in Florida.

Was this an honest lack of communications between departments or a strategic decision by Lincoln to provoke the Confederacy into war? One can only speculate.

April 2

It was a rainy, windy Tuesday, and the captain of the merchant schooner Rhoda H. Shannon, which had departed Boston to deliver a shipment of ice to Savannah, requested a weather update. The report would prove unreliable.

April 3

As the weather got worse, the Shannon became disoriented. Around 3 p.m. its captain mistook Charleston Harbor as the entrance to Tybee Island at the mouth of the Savannah River, which he blamed on faulty navigational equipment and a heavy gale.

He raised the U.S. flag per protocol for a ship requesting a local pilot to come aboard to bring the schooner in safely. When no one responded, he decided to pilot the ship into the harbor himself.

Lt. Col. W.G. DeSaussure, commander of Confederate batteries on Morris Island, had orders to prevent any ship flying the U.S. flag from entering the harbor. As the Shannon passed by, DeSaussure’s troops fired three warning shots across its bow. The Shannon dropped anchor.

DeSaussure sent a skiff to assess damage to the schooner and its crew. Watching the situation unfold from Fort Sumter, an alarmed Anderson did the same.

The captain explained his mistake to both, who expressed relief that no one had been injured nor the schooner seriously damaged. DeSaussure said the Shannon could lie at anchor until the foul weather passed. The scouts returned to their bases.

Once the weather cleared, the Shannon quietly left.

April 4

Lincoln met with naval Capt. Gustavus V. Fox to review a plan for handling “the Sumter situation.” Though details of the secret meeting are unknown, Lincoln afterward announced he would send a naval expedition to resupply Fort Sumter, notifying Gov. Pickens of its arrival.

Cabinet members cautioned against notifying the governor, but Lincoln was adamant, as doing so was key to his secretive plan.

April 5

Secretary of State Seward and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles realized each had planned a secret mission spearheaded by the warship Pohowtan using different captains going to different destinations.

Shortly before midnight, they took their unsettled argument to Lincoln, who was working late. Initially, Lincoln sided with Seward’s mission to Florida, yet after Welles produced copies of his orders, Lincoln agreed the Powhatan should go to Charleston. Welles did not telegram New York shipyard’s Capt. Andrew Foote with confirmation until the next morning.

April 6

Capt. Foote was torn between his two superiors. He chose to prioritize the orders he had received directly from President Lincoln, dispatching a large naval expedition including several merchant ships, warships carrying 300 to 500 men and arms, and tugboats to land reinforcements at Fort Sumter (sources differ on exact numbers). Welles’ telegram did not reach him until after the expedition left heading south.

Lincoln sent a message to Anderson in his own handwriting, saying to “... expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only; and that, if such an attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice.” A copy also went to S.C. Gov. Pickens.

Rosen calls the note’s wording “a masterpiece of ambiguity.” To Northern readers the message implied the government was on a humanitarian mission taking food and medicine to hungry men. To President Davis and Gov. Pickens, however, the message not only said provisions would be sent to Fort Sumter, which Pickens had forbade, it also indicated force would be used if they did not allow it. Surely that was why warships were included in the expedition.

Or was it?

No one, not even Secretary Seward, knew Lincoln had secretly given orders to have the warships pass by Charleston and continue to Florida.

Davis and Pickens now had two options: either capture Fort Sumter before those ships arrived or, they incorrectly assumed, allow armed warships to enter Charleston Harbor.

April 7

S.C. Gov. Francis Pickens’ 54th birthday was a difficult one.

He received Lincoln’s message saying as long as local authorities did not try to stop the resupply effort, the expedition would not land reinforcements. If, however, Pickens interfered with their mission, Federal troops would defend their ships.

And what about Lincoln’s assurance that “no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice?” Might he move his warships into position, then suddenly “give further notice?”

Pickens could not allow Federal troops to maintain a presence in Charleston Harbor. Yet neither did he want his legacy to be the one responsible for starting the American Civil War.

Historians still debate the meaning of Lincoln’s message. Many insist we should not try to “read between the lines” when interpreting history. Others say Lincoln’s message was clearly provocative, forcing the Confederacy to attack.

Meanwhile, the first tugboat to land supplies – and soldiers if necessary – departed New York.

April 8

The armed revenue cutter Harriet Lane left New York heading south, as did a second tugboat.

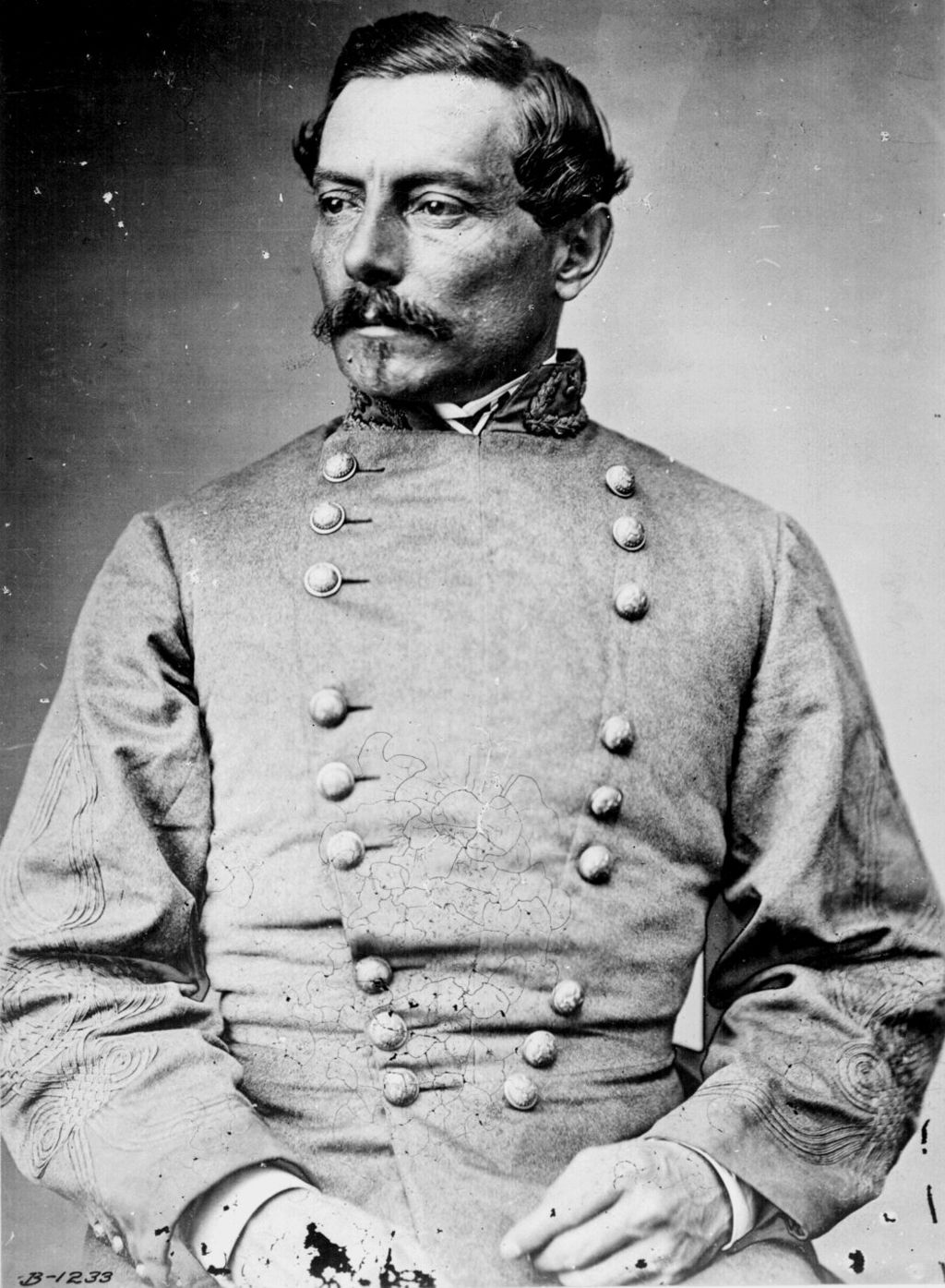

That evening, Pickens and Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard notified President Jefferson Davis of Lincoln’s message. Davis immediately instructed Beauregard that under no circumstances was he to allow provisions to reach Fort Sumter.

April 9

The Pawnee, the U.S. Navy’s heaviest sloop of war, left Washington heading south.

The Confederate Cabinet, meeting in Montgomery, decided to capture Fort Sumter before the expedition arrived.

April 10

The Pocahontas, with 95 men and six cannons, departed Norfolk, heading south.

Confederate Secretary of State Robert Augustus Toombs wired Beauregard with orders to demand Anderson’s surrender, or else once he was certain the fort was about to be resupplied, to open fire. Beauregard replied that he would demand the surrender tomorrow at noon.

April 11

Around noon, three of Beauregard’s aides rowed to Fort Sumter with his demand to evacuate.

Diarist Emma Holmes, who lived at 19 East Battery, wrote: “A day never to be forgotten in the annals of Charleston … the whole afternoon & night, the Battery was thronged with spectators of every age and sex, anxiously awaiting with the momentary expectation of hearing the war of cannon opening on the fort or on the fleet which was reported outside the bar. Everybody was restless and all who could go were out.”

After consulting with his officers, around 4 p.m. Anderson replied to Beauregard, who once had been a student of his at West Point: “I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication demanding the evacuation of this fort, and to say, in reply thereto, that it is a demand with which I regret that my sense of honor, and of my obligations to my Government, prevent my compliance.”

Shortly before midnight, the Harriet Lane anchored off Charleston Harbor.

April 12

Soon after the Harriet Lane’s arrival, the supply ship Baltic and warship Pawnee joined it off Charleston Harbor’s bar.

The Confederate delegation left Fort Sumter in the early morning hours to notify Beauregard that Anderson had rejected the ultimatum. With the Federal naval expedition now outside the harbor, time was up for Beauregard.

Around 3 a.m., he sent Col. James Chesnut back to Sumter with his final message: “I am ordered by the Government of the Confederate States to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter. My aides, Colonel Chesnut and Captain Lee, are authorized to make such demand of you. All proper facilities will be afforded for the removal of yourself and your command, together with company arms and property, to any post in the United States which you may select. The flag which you have upheld so long and with so much fortitude, under the most trying circumstances, may be saluted by you taking it down. Colonel Chesnut and Captain Lee will for a reasonable time await your answer. I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant.”

Anderson reaffirmed he would follow his orders not to surrender the fort, closing his message with “Thanking you for the fair, manly and courteous terms proposed and for the high compliment paid me.”

As Beauregard had empowered him, Chesnut responded: “SIR: By authority of Brigadier-General Beauregard, commanding the provisional forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time.”

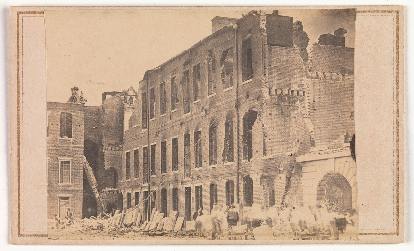

At 4:30 a.m. a ceremonial signal shot from Fort Johnson exploded far above Sumter. Ten minutes later, the Morris Island batteries opened fire.

Rather than assist Anderson with the fort’s defense, as one would expect, the Federal ships waiting outside the harbor turned and left, having made no attempt to resupply Fort Sumter.

The battle lasted 34 hours before Anderson surrendered. Despite the attack’s intensity, no one on either side was killed, nor even seriously wounded. True to his word, Beauregard allowed Anderson to strike the Federal colors ceremoniously. The Union soldiers then boarded a ship to New York, where they were welcomed as heroes.

The Civil War had begun.