JANUARY 9, 1861

Most folks will tell you the Civil War began April 12, 1861, with the first shots fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Many historians, however, say the war actually began 164 years ago this week, Jan. 5-9, 1861.

To pick up where we left off in our last column, Maj. Robert Anderson had secretly evacuated his 85 or so troops from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter on Dec. 26, 1860, a week after South Carolina seceded from the United States.

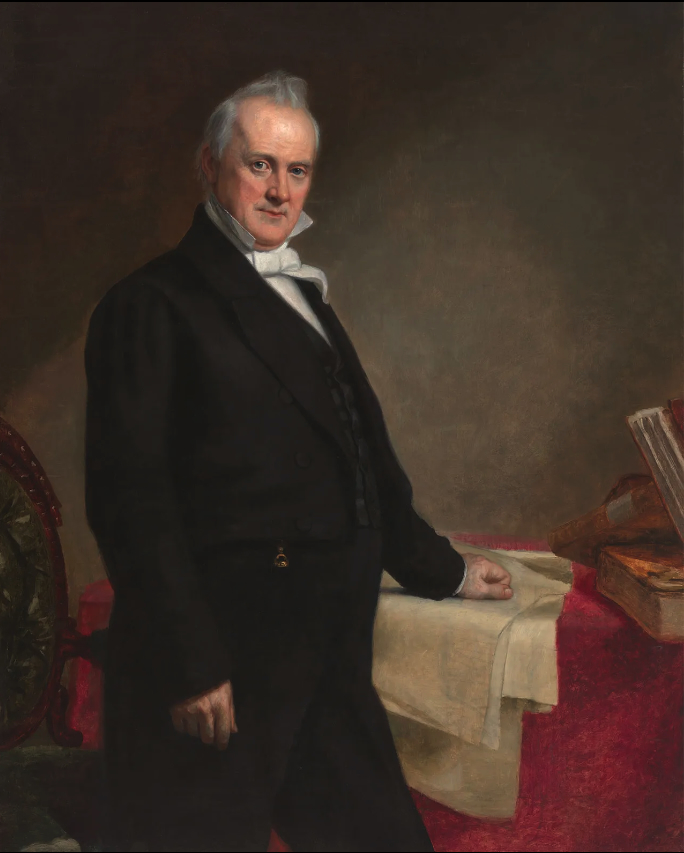

State representatives had met both before and after the secession vote with President James Buchanan, demanding he withdraw federal troops from Charleston and surrender all forts and other government property. They left those meetings believing they had an agreement with the President that both sides would maintain the status quo until a peaceful transfer of property could be negotiated. The U.S. would not reinforce Anderson’s garrison, Buchanan implied, in return for South Carolina’s not attacking them. He agreed to give advance notice if anything changed.

From this conversation, the South Carolinians inferred that the federal government would agree to a non-violent secession.

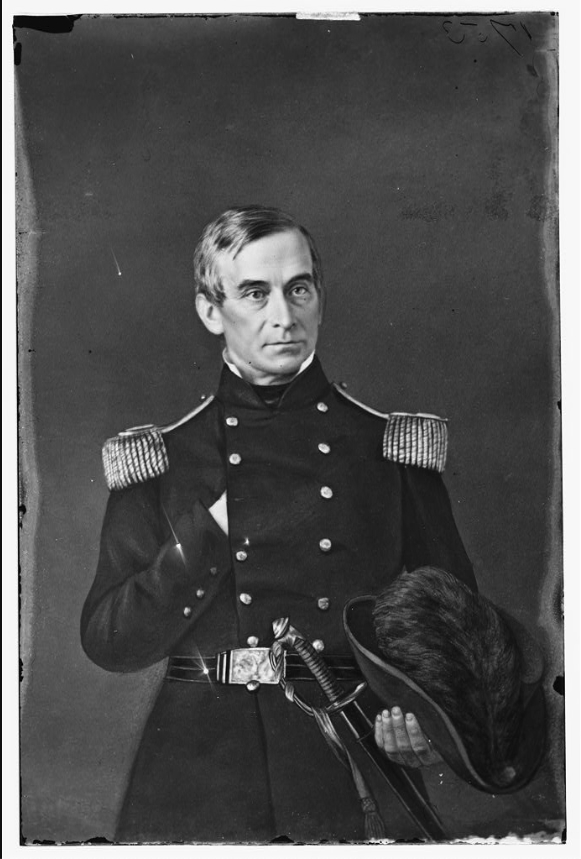

No evidence indicates Maj. Anderson was aware of such an agreement. He was instructed by U.S. Secretary of War John B. Floyd to occupy whichever Charleston fort seemed most defendable and avoid provoking the Carolinians. If, however, he was attacked, he was to defend his position. Following those orders, he chose to evacuate without notifying Washington first.

A Dec. 27 message from Anderson to Floyd confirmed he had “abandoned Fort Moultrie because I was certain that if attacked my men must have been sacrificed, and the command of the harbor lost. I spiked the guns and destroyed the carriages to keep the guns from being used against us.” He said he had enough food, medicine, and military supplies for about four months.

Carolinians were furious, believing Anderson had breached their agreement with Buchanan to maintain the status quo. They immediately mobilized local militia including the Washington Light Infantry, Palmetto Guard, Cadet Riflemen, and others who, over the next several days, seized the Customs House, Arsenal, forts Moultrie and Johnson, Castle Pinckney, and other government properties.

South Carolinians justified their actions by saying Buchanan had reneged on his promises. Federal officials, however, with no written agreement, considered the state’s forceful seizure of government properties an act of war, noting Anderson’s evacuation had been a defensive tactic posing no threat to Charlestonians.

Buchanan considered ordering Anderson back to Moultrie to mollify the Carolinians and blaming the major for acting without proper authority, even though Floyd’s orders had clearly given him that authority. Political pressure to forcefully respond to the property seizures, however, eliminated that option.

Buchanan met with the S.C. delegation after receiving Anderson’s notification, listening to their complaints without saying much. The next day, Dec. 28, he wrote using courteous, but firm language that he considered the seizures an act of hostility. The United States, he proclaimed, would hold Fort Sumter by all means possible.

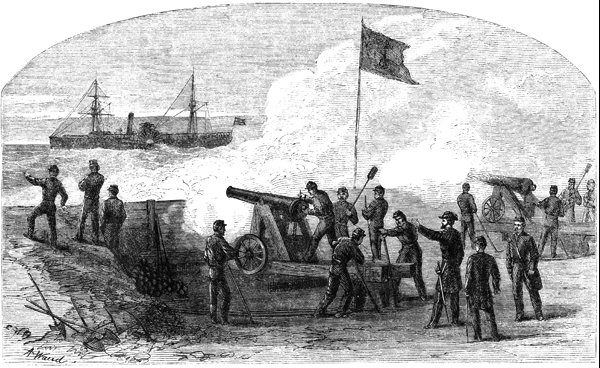

S.C. Gov. Francis Pickens announced he would not allow any U.S. ship to enter Charleston Harbor. He ordered both the militia at Fort Moultrie and a small unit of Citadel cadets whom he had sent to Morris Island to enforce that order.

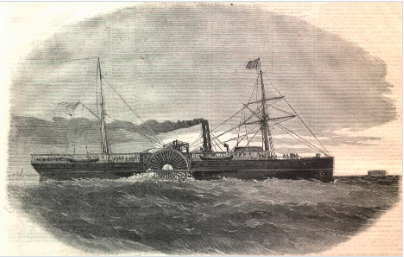

On New Year’s Eve, Buchanan decided to send reinforcements to Anderson, something he had been considering since early fall. Rather than a military ship, however, on Jan. 5 the merchant steamer Star of the West left New York’s harbor. Though the mission was shrouded in secrecy, most sources say that while the Star left its berth with only supplies aboard, it shortly thereafter picked up more than 200 recruits from tugboats before heading to Fort Sumter.

Simultaneously, Maj. Anderson telegraphed Washington saying that while South Carolina was erecting batteries, he felt safe for the time being at Fort Sumter. After receiving Anderson’s message, Buchanan dispatched the warship Brooklyn to intercept the Star with orders to return, but it was too late.

The Star, sailing under the U.S. flag, arrived outside Charleston’s harbor just after midnight on Jan. 9, where it sat silently until daybreak. Any recruits aboard were ordered below deck; the ship looked like the simple merchant vessel she was.

That night, as he watched the naval drama unfold before him, Maj. Anderson had to make another historic decision. Should he take action to defend the Star or continue to do nothing to provoke the Carolinians, as his orders from Washington had said? He prepared to cover the ship, his men posted at the ready. Then he waited.

At dawn, as Star of the West began crossing the harbor’s bar, the cadets fired across its bow, initiating cannon fire from Fort Moultrie. Though a few shots hit the ship, no serious damage or injuries were incurred. The Star quickly turned around and headed back to New York. Anderson undoubtedly let out a sigh of relief and told his men to stand down. His caution and patience had, for the second time, avoided initiating a battle.

Meanwhile, warranted or not, South Carolina had fired the first shots of the Civil War at an apparently unarmed supply ship on Jan. 9.