INFLUENCE OF THE JEWISH CULTURE IN CHARLESTON

Arriving by 1695, Sephardic Jews were among Charles Town's earliest settlers. Originally from Spain and Portugal, many had resettled in the Carribean, England, and the Netherlands before immigrating to Charles Town. Later Ashkenazic Jews from Germany, Poland, and other American colonies joined them.

Charles Town was a hospitable place for Jewish settlement. The liberal Fundamental Constitution of the Carolinas, written by English philosopher John Locke, guaranteed freedom of religion to “Jews, Heathens and other Dissenters from the purity of the Christian religion.” Charles Town's Jewish population enjoyed full citizenship within the colony with the ability to vote, unlike European Jews and most colonists elsewhere in America (though religious tests for voting reappeared from time to time in South Carolina).

Jewish Charlestonians assimilated into the Southern way of life, embracing slavery, racial customs and duelling. Throughout Charleston's history, they have served in a variety of political and civic positions, including the militia. Most Jews supported the American Revolution, and in the 1850s Moses Cohen Mordecai represented Charleston in the State Senate. During the Civil War, Jewish Charlestonians rallied to the Confederate cause. Dozens of young men joined the Confederate Army and several served as officers.

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, an orthodox congregation, had been established by 1749 in a private house on State Street near Queen Street. The Jewish Coming Street cemetery, one of the oldest in North America, was purchased by the DaCosta family in 1754 and transferred to KKBE in 1764.

In 1794 the congregation began building a handsome synagogue on Hasell Street, the interior design of which (fourth image above headline) was based on the great Sephardic Synagogue, Bevis Mark, in London. Its exterior, however, very much resembled a church. The iron gates around the current synagogue on Hasell Street date from this time. This synagogue was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1838 which devastated Ansonborough and surrounding areas.

A new, grander synagogue was built 1840-1841 in the Greek Revival Style. In his dediction speech, the Rev. Gustavus Poznanski declared “This synagogue is our temple, this city our Jerusalem, this happy land, our Palestine.”

In 1824, 24 members of KKBE formed the Reformed Society of Israelites, the first attempt at Reform Judaism in the Western Hemisphere. This group sought to Americanize the traditional Orthodox service by shortening and modernizing the services, using English instead of Hebrew, and including a sermon. In the 1840s KKBE became the first Reform synagogue in the United States. It also added an organ, another first in American Jewish history. These changes caused traditionalists to leave and form another Orthodox congregation.

A predominantly Polish orthodox congregation, B’rith Shalom, was founded in 1854 after a new wave of new Jewish immigrants arrived in the 1840s from the German states and Poland. It eventually made its home on St. Philips Street in 1874.

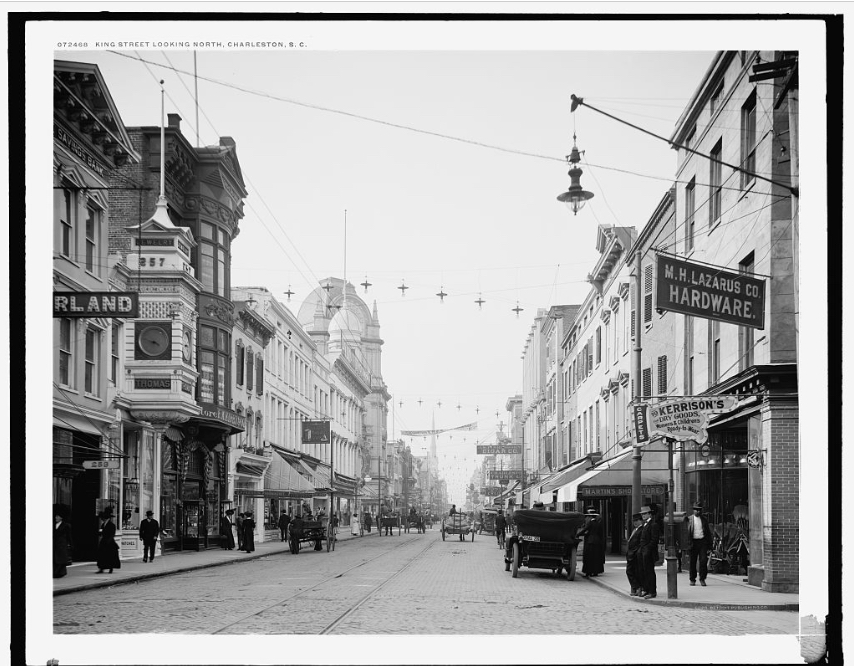

From the 1880s into the 20th century, another immigration wave brought Russian, Polish and Eastern European Jews to Charleston. These settled principally along King and St. Phillips streets and attended the two orthodox synagogues, B’rith Shalom and Beth Israel.

Today there are three congregations in Charleston: Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (Reform) at 90 Hasell St.; B’rith Shalom Beth Israel (Orthodox) at 182 Rutledge Ave.; and Emanu-El (Conservative), founded in 1947 on Gordon Street, but now located in West Ashley.

The Hebrew Benevolent Society (1784)

Founded on June 25, 1784, the Hebrew Benevolent Society of Charleston (Hebra Gemilut Hasadim in Hebrew or literally “Society for Deeds of Loving Kind”) is the oldest Jewish charitable society in the United States. The society’s original seal depicts a skeleton representing the Angel of Death with a scythe in its right hand and an hour glass in its left hand. Its motto, “Tsadakah Tatzil Mi-Mavet,” means “Charity Delivers from Death” (Proverbs 10:2).

Its founders were likely influenced by other local ethnic organizations such as the St. Andrews Society (Scots), Huguenot Society (French Protestants) and Saint George Society (English). Founded shortly after the American Revolution, the Hebrew Benevolent Society's mission, akin to that of other local ethnic societies, was to help the less fortunate Jews of Charleston. It provided aid to those who were sick, indigent or unable to work, as well helped new immigrants become established. They ensured that the dead were buried in accordance with Jewish religious law and tradition. Even into the 20th century, the society helped Jewish refugees from Russia’s pogroms and assisted victims of the 1886 earthquake.

During the 19th century, the society held popular fundraising events such as benefit balls to help the poor. Non-Jewish Charlestonians demonstrated their appreciation for the society's role by supporting its efforts; for example, the St. Andrew’s Society declined any compensation for the use of its hall for the benefit balls. Society members were assigned honorary places alongside other ethnic organizations in John C. Calhoun's funeral procession in 1850.

After the Civil War, when most Charlestonians were economically devastated, the society fell on hard times as well. In an effort to reorganize in October 1866, they sent representatives to New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore to raise money.

In 1994 the society celebrated its 225th anniversary with a traditional, formal, men-only dinner. The society continues its benevolent mission today.

SOURCES AND MORE INFORMATION

"Charleston's Jewish Community" by Robert Rosen, found in the City of Charleston Tour Guide Training Manual, edited by Leigh Handal and Katherine Saunders, 2011. p. 135.

Breibart, Solomon. Explorations in Charleston’s Jewish History (History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2005)

Elzas,Barnett Abraham. The Jews of South Carolina: from the earliest times to the present day

Hagy, James This Happy Land: The Jews of Colonial and Antebellum Charleston (University of Alabama Press, 1993)

Handal, Leigh. Lost Charleston (London: Pavilion Publishing, 2019) p. 86.

Rosengarten, Theodore and Dale Rosengarten. A Portion of the People: Three Hundred Years of Southern Jewish Life. McKissick Museum, corporate author.

Rosen, Robert. Jewish Confederates. (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2000)

The Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina

Tobias, Thomas J. The Hebrew Benevolent Society of Charleston, S.C. (Charleston, SC, 1965)

Site of the former Hebrew Orphanage at 88 Broad Street

Hebrew Orphan Society (1801)

The historic marker at 88 Broad Street can be a bit misleading. Its 1801 date refers not to the building, but to the founding on July 15 of the Hebrew Orphan Society of Charleston, America’s oldest incorporated Jewish charitable organization.

The building was constructed between 1793 and 1811, most likely by Henry Laurens. An excellent example of neoclassical design, its first two occupants were banks, after which it became offices. Yet the building’s history is most closely associated with the Orphan Society, which purchased it in 1833.

Charleston had the largest Jewish community in the United States when 23 Jewish men founded The Hebrew Orphan Society. The society was incorporated in 1802 as the Abi Yetomin Ubne Ebyonim, or Society for the Relief of Orphans and Children of Indigent Parents. Its purpose was to provide education, clothing and support for widows, orphans and children of indigent parents.

For nearly a century, the society used the building for meeting and classroom space, preferring to place orphans in private homes – widely considered a best practice today. Serving both orphans and the poor, the Society’s school identified and cultivated students’ individual talents in the arts and sciences, believing that being academically gifted was not the sole purview of the wellborn. The building also served as a center of Jewish culture and influence, as well as temporary meeting space for Congregation Beth Elohim after its synagogue burned in 1838.

In 1860, several orphans were housed here, though they were evacuated in 1862 to an undisclosed location (some believe Columbia). They never returned, though by 1866 the society again occupied the building. The Earthquake of 1886 left at least four Jewish children orphaned. They were sent to a Hebrew orphanage in Baltimore with a message that a facility for parentless Jewish children was no longer available in Charleston.