SEWEE SHELL RING

Charleston has lost many of its historical and architectural treasures over the centuries, but none older or perhaps less understood than the Sewee Shell Ring found in Awendaw.

This pre-historic construction has never been definitively dated, but some sources suggest it was created by one of the earliest homo sapien groups to settle along the Southeast coast of North America about 4,000 years ago. If so, it could be even older than the great Giza pyramids.

Among the earliest evidence of human settlement in the Southeast, these shell rings are nearly all that remains of a once-vibrant Native American culture that lasted for centuries. Though archeologists are coming to understand more about the physical nature of these structures every day, their purpose remains a mystery.

Another mystery is that shell rings are found in only four disparate places in the world: Japan, Colombia, Peru and the southeastern United States. The Sewee Ring (spelled variously as SeeWee or SeWee) is the northernmost of nearly 60 rings found in North America. Some of these form complete circular rings, while others have distinct openings along their wall. Sometimes the openings face the estuary, as does Sewee’s, though further south they often open onto the mainland sidie of the ring.

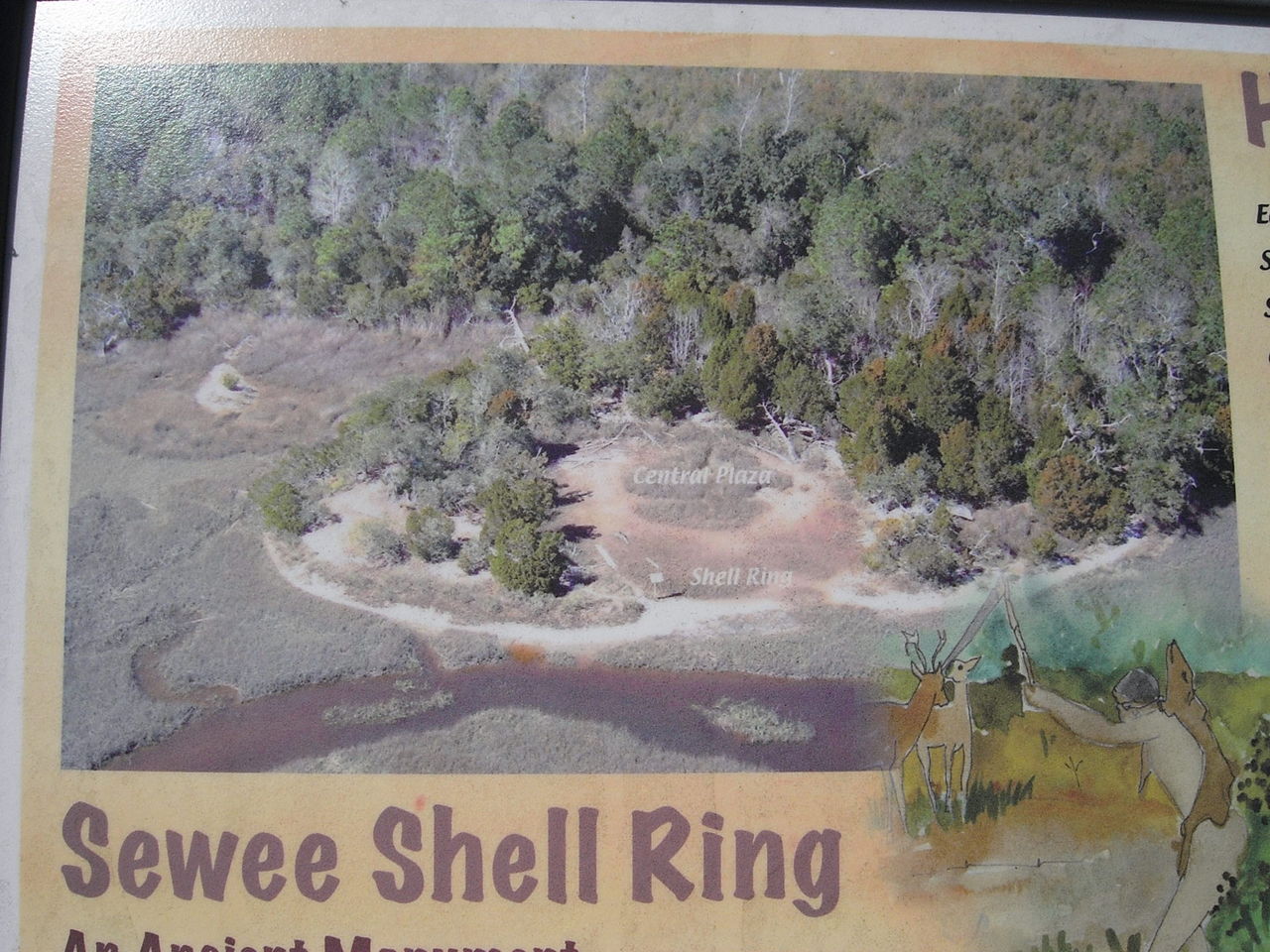

Some, like Sewee, are nearly circular as in the letter C; others are more oval, looking more like a U. Again like Sewee, some stand alone while others are made up of multiple rings. The diameter of Sewee's ring is about 150 feet, smaller than the general average of 225 feet. Its walls are believed to have been 10 feet high, again average, though Sewee’s were steeper than most others.

Despite these differences, they all feature a distinctive wall surrounding an open plaza that was cleared of debris. The walls are made mostly of oyster shells, along with mussels, clams and periwinkles mixed in. They also contain the occasional pottery shard, early tools, and bone fragments, leading archaeologists to conclude that their builders hunted, fished and raised their families during a time when their culture was transitioning from independent egalitarianism to a social community hierarchy.

In addition, these bone fragments also shed light on the domestication of dogs in North America. Unlike most rings, a few human remains with evidence of cutting or burning, have been found in Sewee’s ring. This has lead some researchers to suggest cannibalistic theories, though that is debated by many.

Though theories abound, no one has yet established why these structures were built, what purpose they served. Were they residential? Though some arguments can be made,that seems unlikely at Sewee because of its steep sides. Did they serve a civic, ceremonial or religious purpose? Perhaps they were some type of recreational field such as the Mayans created? No one knows.

What archeologists do know is that the structures are not rubbish heaps, similar to the mound of oyster shells at Charleston's White Point Gardens, which greeted the first permanent European settlers to sail into Charleston Harbor in 1670. Archaeological evidence clearly imply that rings such as Sewee’s were purposely and thoughtfully created within a relatively short time.

As today, any built structure in the Lowcountry's hot, humid, and storm-prone climate faces challenges. The Sewee shell ring has been damaged over the centuries by hurricanes, forest fires, erosion and sea-level rise. Yet perhaps the greatest contributor to its demise was its uninformed discovery by transportation workers in the late 1920s, who unfortunately mined nearly half the site for building materials to pave Highway 17 for smoother automobile travel. They had no idea what they were destroying.

Today, the boardwalk that surrounds the ring's remains provides some of the most tranquil views in the South Carolina Lowcountry, an idyllic setting with soaring, graceful shorebirds and the clacking of little crab claws from those that make their home in the pluff mud surrounding the ring’s edge. The rings look quite striking in aerial views. Yet when viewing the site at ground level without interpretive signage, visitors who hike the mile or so from Highway 17 to the site might never even realize its remains are there in front of them.

Sources and More Information: