SEPTIMA POINSETTE CLARK (1898 - 1987)

Certainly there are many, many people who say they have been inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Yet relatively few people have heard the story of a woman who, Dr. King said, inspired him: Septima Poinsette Clark. Her name might ring a bell for those who regularly drive the Crosstown, formally named the Septima P. Clark Parkway.

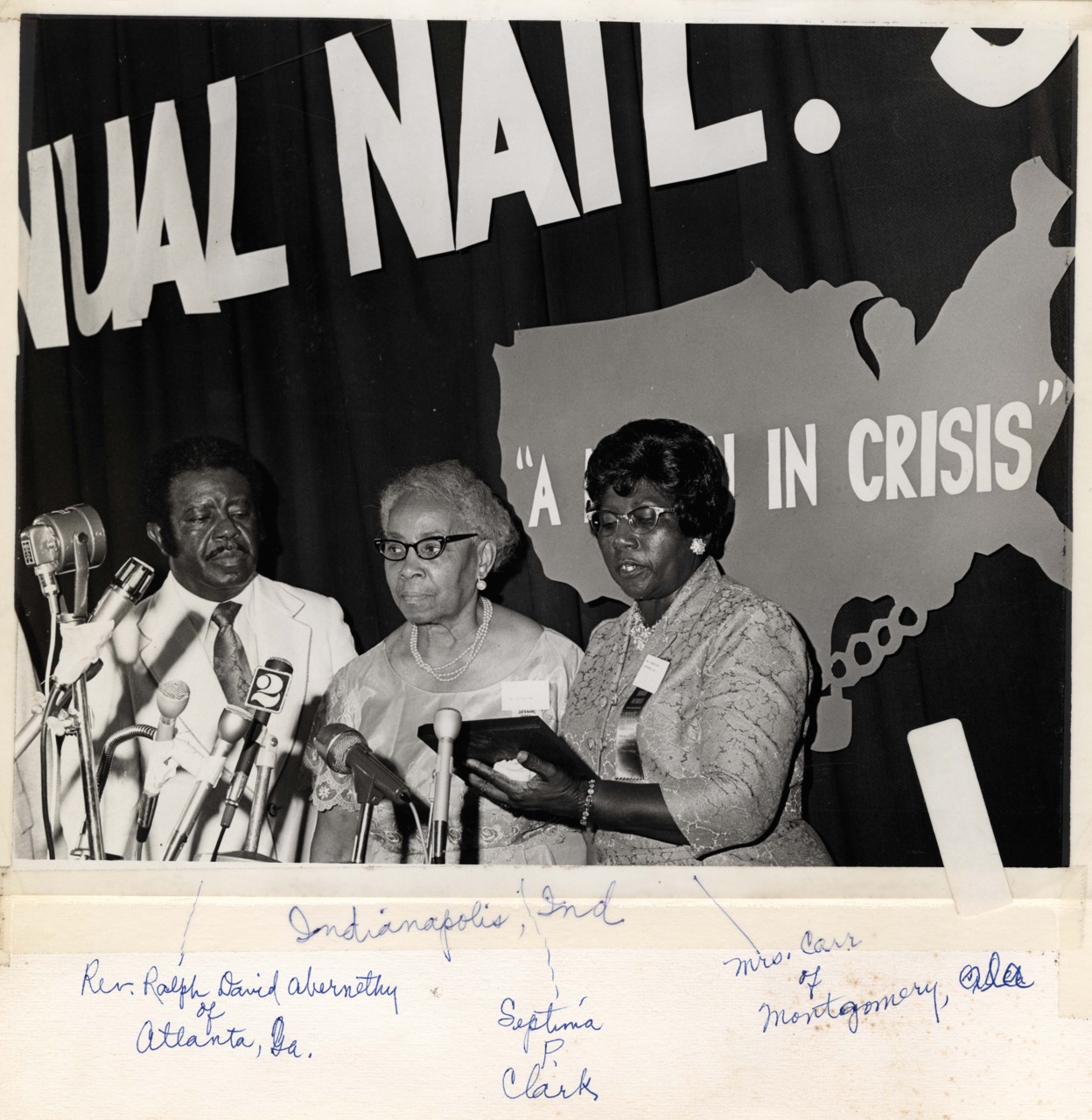

Though they had their differences, King invited Mrs. Clark to accompany him to Sweden when he went to accept the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, noting in his speech that this American educator and early civil rights activist had been an inspiration to him.

Septima Poinsette was born May 3, 1898, to Peter and Victoria Warren Anderson Poinsette. Peter had been born a slave on Joel Poinsette's farm near Georgetown on the Waccamaw River. A house slave, Peter's principal responsibility was getting the children to and from school.

Upon emancipation, Peter took a job working on ships in Charleston Harbor. During one of his travels to Haiti, he met Victoria, who had been born a free person of color in Charleston, but moved to Haiti as a young child to be raised by her brother. Peter and Victoria returned to Charleston and Victoria took a job as a laundress, declaring proudly that she had never been, nor would ever be, anyone's servant.

Victoria was a strict mother, particularly on her daughters, and was determined that they would grow up to be ladies. They were allowed to play with friends just one day a week, with the other six being devoted to their lessons and their chores. They were admonished to never go out without their gloves, to never yell or scream, and to never eat standing on the street rather than seated properly at a table. Septima's father, however, was more lenient and she recalled being disciplined by him only once: when she tried to skip school one day.

Septima began school in 1904 when she was six, attending the Mary Street School. Her parents, however, felt that she was not learning much and enrolled her with a private teacher who lived across the street from the school. Because her parents were too poor to pay for her education, Septima babysat for the tutor's children in lieu of tuition.

When Septima graduated from sixth grade, there was no public high school for black children in Charleston. Nevertheless, she passed an exam that allowed her to begin attending 9th grade at Avery Academy, a high school founded by missionaries from Massachusetts. Initially all of her teachers were white women whom she admired and sought to emulate. In 1914, two years before Septima's graduation, the first black teachers were hired at Avery, and this undoubtedly nurtured her desire to teach.

There was no money for Septima to continue her studies once she graduated from Avery. Thus at 18, she passed an exam that qualified her to teach children in the rural community of Johns Island. Perhaps as importantly, in the evenings she voluntarily taught adults literacy and basic skills, as South Carolina sought to suppress Black participation in the electoral process by requiring voters be able to read, write, and explain the state constitution. With few resources, Clark often used the Sears catalog as a teaching tool. After three years in this position, she returned to teach at Avery.

Mrs. Clark made $35 a week teaching 132 rural black children. Her assistant teacher earned $25. Meanwhile the white teacher across the street was earning $85 teaching three white children. Unwilling to accept this disparity, Clark moved to Columbia where she taught and became involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). As vice president of the state’s chapter, Clark worked to address educational disparities.

She used her earnings to attend Benedict College in Columbia part time. She eventually went on to earn her master's degree at Hampton Institute in Virginia.

She married a man from out of state, Nerie David Clark. Her mother never forgave her for marrying a man she deemed to be "a stranger." Mr. Clark did not live long after their marriage, during which the couple had two children, only one of whom survived.

Following her husband’s death a year after their second child was born, Septima returned to Johns Island to teach children during the day, then voluntarily taught adults literacy and basic skills during the evenings. Although she had her master's degree by this time, Charleston did not hire black teachers at that time.

In 1955, South Carolina passed a law banning city and state employees from being members of the NAACP. Clark refused to resign her position and was fired by the Charleston County School Board, losing her pension after teaching nearly 40 years. Forty-one teachers stood with her and lost their jobs too, demonstrating their willingness to fight for what they felt was right.

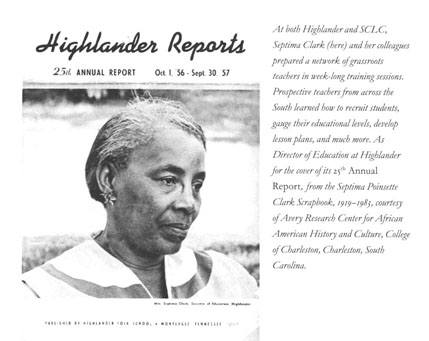

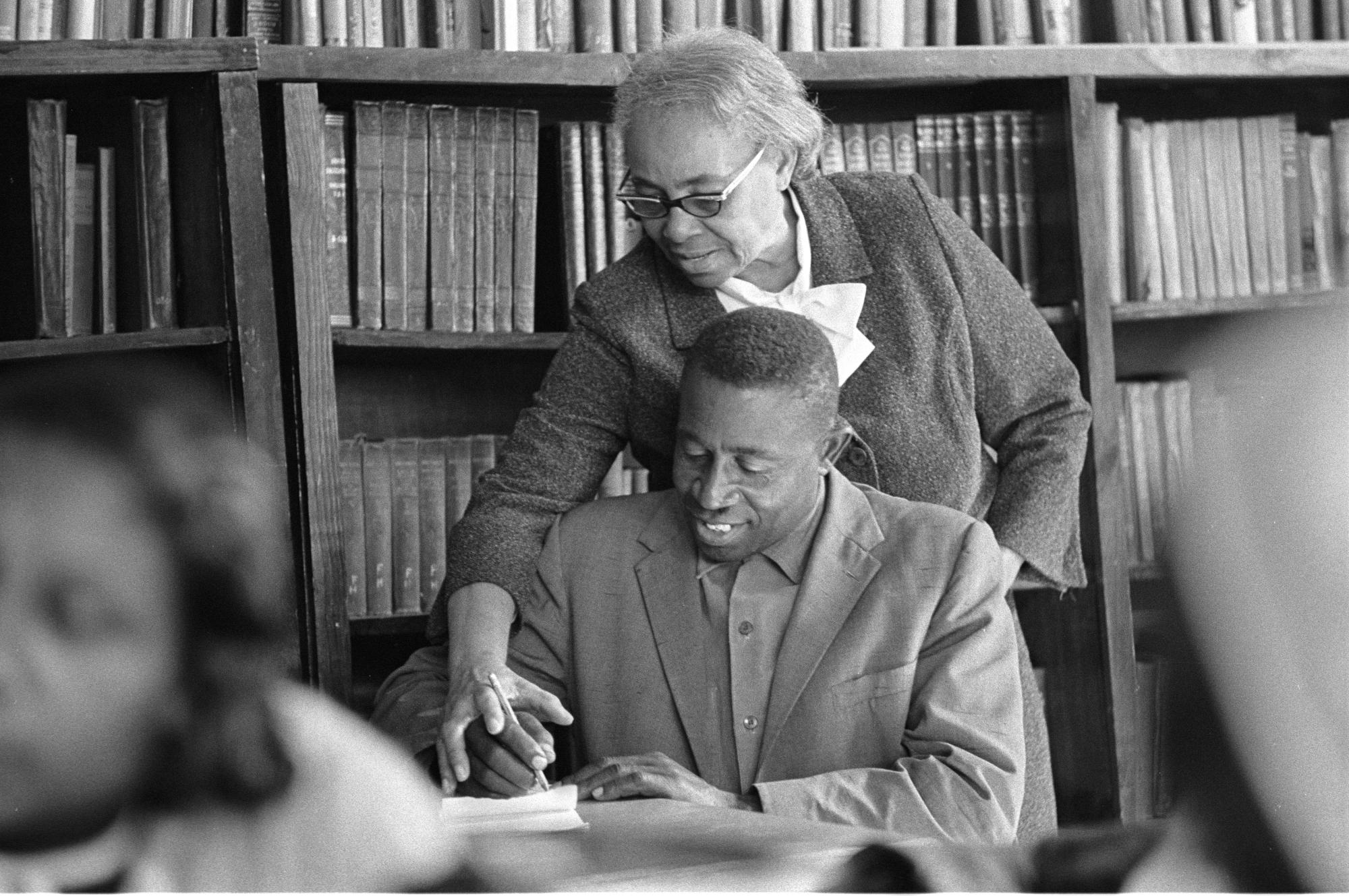

She then went to Tennessee and began teaching at the Highlander Folk School, teaching illiterate sharecroppers to read, fill out driver's license exams and voter registration forms, and sign checks. This was especially important as some states required literacy and the ability to interpret portions of the U.S. Constitution as prerequisites to voting.

Her work, some of which was conducted alongside Thurgood Marshall, who would become the first black U.S. Supreme Court Justice, would help lay the foundation for the eventual desegregation of public schools. One of her students at Highlander was Rosa Parks (at right).

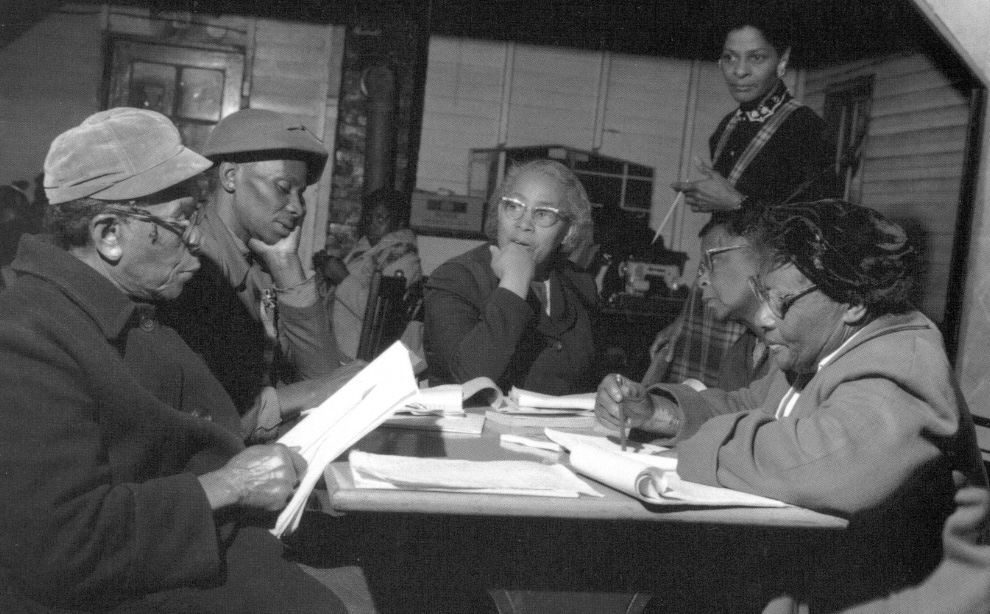

After Tennessee closed the Highlander School in 1961, Clark was hired by King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to help create a network of "Citizenship Schools" based on the Highlander model, empowering the Black community not only by teaching them how to read and write but also by engendering pride in oneself and one's culture and an understanding of one's rights as a U.S. citizen.

Former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young once said the citizenship education program Clark helped establish was the foundation of the Civil Rights movement. King himself called Clark the “Mother of the Movement.”

This was the crossroads of her most important work with MLK, teaching people how to act collectively and protest nonviolently against racism. It has been estimated that by 1969, Mrs. Clark had been instrumental in registering 700,000 voters.

Still, Clark had her qualms with King, accusing him of gender discrimination. In her autobiography, Clark wrote that denying women the same equality King sought for Black men was "one of the greatest weaknesses of the civil rights movement."

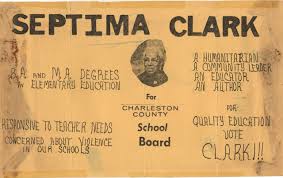

Upon her retirement, Mrs. Clark sued for reinstatement of the pension she lost when she was fired in 1956. She got it and went on to serve two terms on the Charleston County School Board, the same institution that had fired her so long ago. She was also awarded the Order of the Palmetto, South Carolina's highest civilian honor.

Septima P. Clark died on Dec. 15, 1987, and is buried at Old Bethel Methodist Church on Calhoun Street. One of Charleston's most prominent thoroughfares, the Septima P. Clark Parkway (commonly referred to as the Crosstown) was named in her honor, as was Septima P. Clark Academy on James Island.

SOURCES & MORE INFORMATION