DANCE O' THE HEMPEN JIG: CHARLESTON'S PIRATICAL HEYDAY

Pirates weren’t always the bad guys - at least not if you asked the merchants along East Bay and Tradd streets during Charles Town’s piratical heyday, from its founding in 1670 through the first two decades of the 18th century. In those days, Charles Town was a favorite port for privateers looking to sell stolen goods at reasonable prices.

Privateering, that is the looting of foreign ships during times of war (and in those days when wasn’t a war going on among European countries fighting for possession of the New World?), was legal as long as one obtained a license from one’s own government to raid the ships of combatant counties. The War of Spanish Succession (1702-1713), known in Charles Town as Queen Anne’s War, was one such conflict fought among the English, Spanish and French over disputed rights to colonial territories. During that war, it was common for each nation to issue its warships licenses to attack and plunder enemy ships, a very lucrative venture.1 In a sense, the trade could almost be deemed patriotic: “our” good guys attacking “their” bad guys - with legitimacy, of course, varying with which side you were on.

Meanwhile, despite the typical settlement hardships and epidemics, Charles Town was thriving and growing as the 18th century dawned. Barbadian traders were pushing the edge of the colony’s frontier ever more up and inland along the western branch of the Cooper River. French Huguenots, who had arrived a decade or so earlier, were developing burgeoning rice and indigo plantations along the coast’s edge, establishing the foundation on which South Carolina’s storied plantation society would be built. Situated as it was at the western terminus of the Great Atlantic Highway, Charles Town’s harbor was filled with ships and robust economic opportunities.

Within this context, privateers arrived in Charles Town flush with purses full of “hard money” -- gold and silver coins -- and they spent lavishly on food, drink, supplies, accommodations, entertainment and other goods while in port. In addition, Charlestonians relied on the privateers, “private men of war [with] letters of marque from Great Britain,”2 to help protect them against French and Spanish marauders seeking to claim the English colony.

Admittedly the seamen could be a rowdy bunch more often than not, prone to fighting, damaging property, intimidating locals, and too often leering at respectable young women. Though good for the local economy, they also brought trouble, a general concern or uneasiness, along with them while in port. The privateers’ disruption of lawfully taxed trade became a concern for the Lords Proprietors early on. As early as 1684, England’s Privy Council passed an act mandating that the colony suppress any and all illegal maritime trade.

Yet not much changed as a result of the act. Local officials were slow to arrest the privateers, and thereby interfere with their impact on the local economy, nor were they hasty to investigate the legality of the mariners’ supply chain. One Charles Town merchant reacted to the Privy Council’s Act by complaining that anyone who cracked down on pirates were “Enemys of the Countrey.”3 For the most part, customs officials were willing to accept bribes to allow Charles Town’s merchants and privateers to continue doing business as usual. And so, against the British Privy Council’s edict, Charlestonians continued to trade with these “cutthroats [who] were also cut-rate traders, and London wasn’t sending them any cheaper supplies.”4

But that perspective was about to change.

The Peace of Utrech, reached in 1713, brought an end to Queen Anne’s War, and with it the end of government-sanctioned privateers’ licenses. The marauders of the sea suddenly found themselves out of a job, one which they had enjoyed and profited from immensely. Many, if not most, were unwilling to settle for more mundane, lower-paying occupations back on land, and so they continued their pillaging industry by raiding any ships they came across, regardless of which nation’s flag it flew. Formerly legal privateers now became full-fledged pirates, sea-faring thieves who ruthlessly plundered, kidnapped, killed and raped at will, operating entirely outside of any country’s law.

Their attacks reached their peak along the Carolina coast in the late 1710s, when captains such as Edward Teach, Stede Bonnet, Richard Worley and Charles Vane began sacking local ships carrying rice, indigo and other trade goods between Charles Town and European markets. Now not only were the buccaneers interrupting commerce, the pirates had also begun to threaten lives and undermine the economic and political stability of the colony.5 Once Charlestonians became the victims, rather than the beneficiaries, of the pirates’ looting, public support for them quickly reversed itself. By 1716, Charlestonians, even the merchants, had had it with these guys.

In 1716, the colony was recovering from a victorious, but devastating war with the native Yemassee tribes the previous year. Politically powerful Barbadian traders, known as the Goose Creek Men, had prevailed upon the colony’s Lords Proprietors to send help and supplies to defeat the Yemassee, but it never came. (The British Proprietors wryly responded by reminding the colonists that they had earlier warned them, without effect, that selling local Natives to Carribean slave traders was bound to end badly at some point.) Nor would the Proprietors step in now and rescue the colony from the pirates, this time reminding them of their contempt for the Privy Council’s Act of 1684, banning them from doing business with the privateers. On both counts, the Lords Proprietors said, the colonists had made their own bed and should now not be surprised to have to lie in it.

Proprietary Gov. Robert Johnson stepped up to the challenge. According to one account,6 a group of pirates marooned off the Charles Town coast wandered into town one day seeking help from their old mechant friends. To their surprise, Johnson had them quickly rounded up and hanged within sight of the harbor - a clear message that pirates were no

1. Nicholas Butler, Ph.D. “The Pirate Hunting Excursions of 1718,” Charleston Time Machine podcast, Charleston County Public Library, Nov. 23, 2018.

longer welcomed in Charles Town. In addition, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly prevailed upon Capt. Thomas Howard, commander of the HMS Shoreham, to defend Charlestonians against the “pirates of the Bahamas.”7 By 1718, Col. William Rhett, an officer of the Provincial militia, receiver-general of Carolina, surveyor, controller of customs, and a sea merchant himself, refitted two of his ships, the Henry and the Sea Nymph, with eight guns each and a crew of 60 to 70 men to hunt down the pirates who were terrorizing the Carolina coast.

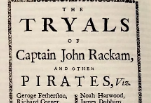

By the fall of 1718, more than 50 sailors had been captured, charged with piracy, and tried before Judge Nicholas Trott in the South Carolina Court of Vice Admiralty. Records detailing the trials of 58 accused pirates document that within the course of 13 trials spread over five weeks in the fall of 1718, only nine defendants were determined to be not guilty and their lives spared.8

The others were all ordered to “dance the hempen jig,” a euphemism for hanging. Many were executed at the site of what is today the city’s beautiful White Point Garden, where they were sometimes left hanging for days to rot in the sun as a warning to anyone who might be thinking of taking up the pirate’s vocation. Others were hanged in chains or displayed in mounted cages, to the same effect.9

Legend, though no hard evidence, holds that many of the pirates who died at White Point were buried in the harbor’s pluff mud below the high tide mark (as burying even executed criminals was still the Christian thing to do), where the incoming tide would naturally unearth the bodies (through no fault of the dutiful local churchmen), leaving them to wash in and out with the currents for days before sinking to their final resting place in the harbor’s bottom.

Most of what we claim to know today of the pirate life comes to us through a few very seasoned storytellers, such as Capt. Charles Johnson, who authored A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates, in 1724. Many have suggested that Capt. Johnson was a nom du plume for Daniel DeFoe, author of the popular Robinson Crusoe, a fictional book published in 1719 and so popular that some credit it as being second only to the Bible in its number of translations. Others suggest the Captain’s true identity to be Nathaniel Mist, an early 18th century London newspaper publisher who wrote regular columns about the great Atlantic pirates of the New World.

Regardless of the author’s identity, these dramatically enhanced stories have shaped the way we think of pirates today, down to the eye-patches, wooden peg legs, and smart-mouthed parrots. Though the tales are woefully short on documentation, the legends have been passed down as history for generations. In a subsequent edition of Pyrates, Capt. Johnson defended his lack of sources, noting that if the reader found the book to be entertaining, “we hope it will not be imputed as a Fault, but as to its Credit.”10 Thus he and other great 18th century storytellers have shaped the world’s memories of life on the high seas for more than three centuries.

Still, the old adage holds true: The truth can sometimes be stranger than fiction.