BIGGIN CHURCH

Biggin Church, today the ruins of St. John’s Berkeley parish church, evokes a peacefulness matched by few other places in the Lowcountry. The site is one with a rich history dating to the earliest days of the Carolina colony.

St. John’s Berkeley was the largest of the first 10 Anglican parishes created by the Church Act of 1706, meaning it was not only a place of worship, but also an entity of the colonial government. Annually elected church wardens and vestrymen served in governmental capacities for a variety of civic duties.

Landgrave John Colleton II, grandson of one of the Lord Proprietors of Carolina Sir John Colleton I, donated 103 acres for the church and its glebe lands. The donation was facilitated by John Harleston, one of the two nephews who inherited Comingtee from Affra Coming.

Three acres set aside for the church was on a bluff Native Americans called Tippicop Haw Hill. The name Biggin came from Biggin Hill, a borough about 15 miles outside London.

Its churchyard includes grave markers of the Huguenots who built the vast rice plantations of the French Santee region, as well as English Barbadians who were among the first to push into Carolina’s interior wilderness. Among its vestrymen were Revolutionary War luminaries Henry Laurens and Gen. William Moultrie, though neither is buried there.

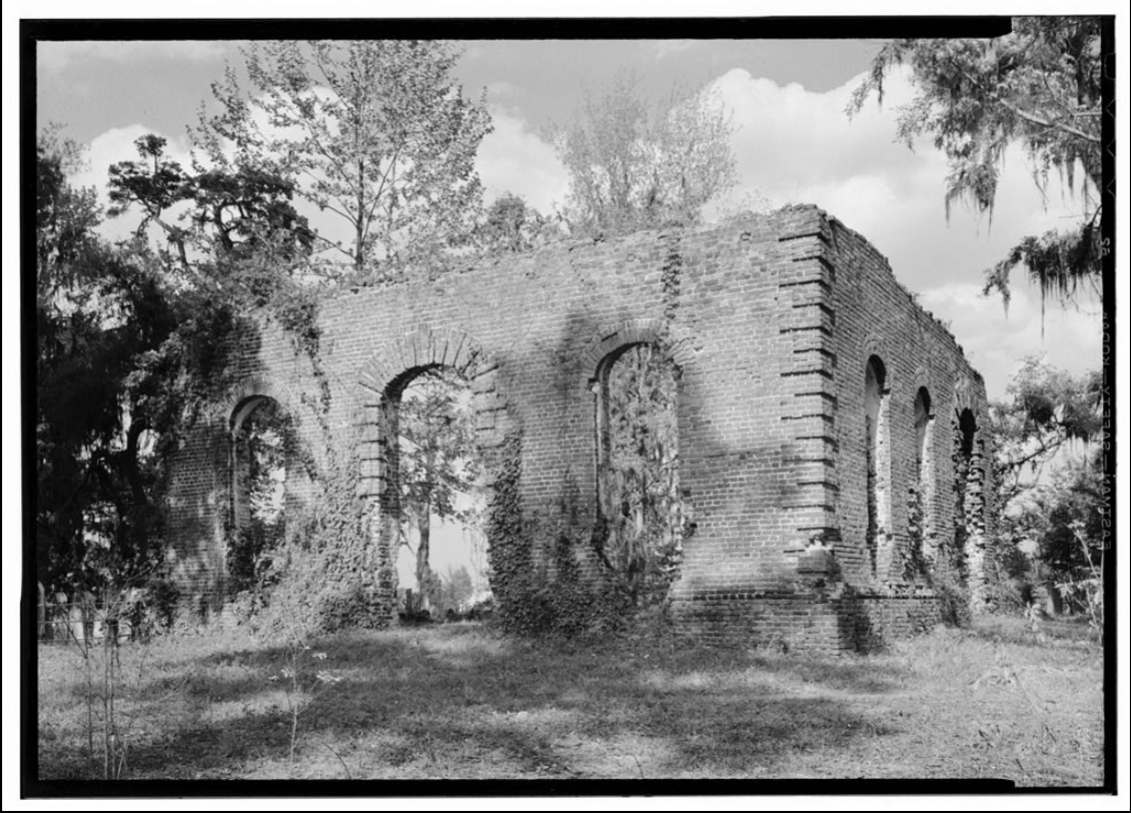

The first wooden church, c. 1711, was destroyed in a 1755 forest fire. By 1761, however, it had been replaced with the grand brick edifice whose ruins remain today. Its sophisticated design and architectural details attest to the wealth and political power of its parishioners.

The rectangular church, about 30’ by 60’, was constructed in a decorative English bond pattern, the sturdiest method of laying brick, which alternated between layers of stretchers (the long side of the brick) and headers (the ends). Its masonry included corner quoins, voussoirs (arched stones) topping the windows, and an impressive water table, a projecting layer of brick near the bottom that deflects rain running down the wall.

Portions of two walls remain, one of which was probably the main entrance as it features a large doorway surrounded by classical architectural elements and was once flanked by two windows on either side.

After the American defeat at the Revolutionary War Battle of Moncks Corner in April 1780, British soldiers stored ammunition in the church. Upon their retreat, they set the church ablaze, blowing out its eastern wall probably as the result of an explosion.

Nevertheless, the other walls remained sound enough to incorporate into its reconstruction shortly thereafter. Gen. Moultrie served on the building committee.

Biggin suffered further damage during the Civil War, when its interior features were either destroyed or stolen. According to an 1868 church report: “Biggin Church was much injured and its walls defaced; all the pews, the desk and chancel rails were torn down and burnt.”

Keating Simons Ball of Comingtee had been entrusted with protecting the parish silver from marauding Union soldiers. He buried the silver, including a chalice brought by Huguenots from France, somewhere on his plantation. Afterward, however, it was nowhere to be found – until December 1946, when Strawberry Chapel's caretaker, Grover Sullivan, and a slave descendant of the Ball family who recalled hearing the story from an ancestor, used a metal detector to find it under a the porch boards of the old rice mill.

Today the silver is kept at The Charleston Museum and used for special services at Strawberry Chapel, one of Biggin’s two rural chapels of ease.

Biggin was never restored after the Civil War. By then, the area’s population had begun moving away from the waterways that had been the colony’s early transportation network and toward areas served by the railroad.

An 1886 forest fire destroyed much of what remained of the church, and its brick walls were ravaged by those scavenging bricks for their own use. By the second half of the 20th century, however, Biggin’s churchyard again began accepting burials, and the scavenging was curtailed.

“For the residents of Berkeley County, it is one of our treasures that reminds us of the rich history of our region,” Berkeley Chamber of Commerce CEO Elaine Morgan told Post and Courier reporter Warren Wise in a 2019 interview. “From before the Revolutionary War through major hurricanes, it remains a legacy of grace of beauty.”