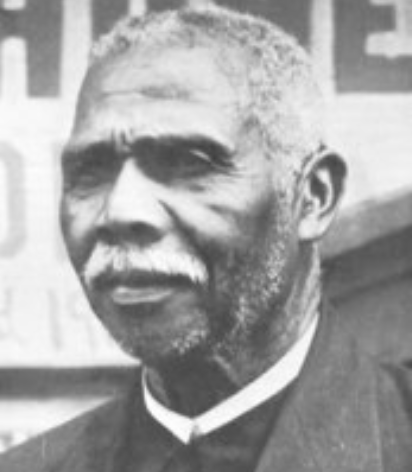

THE REV. DANIEL JENKINS (1862-1937)

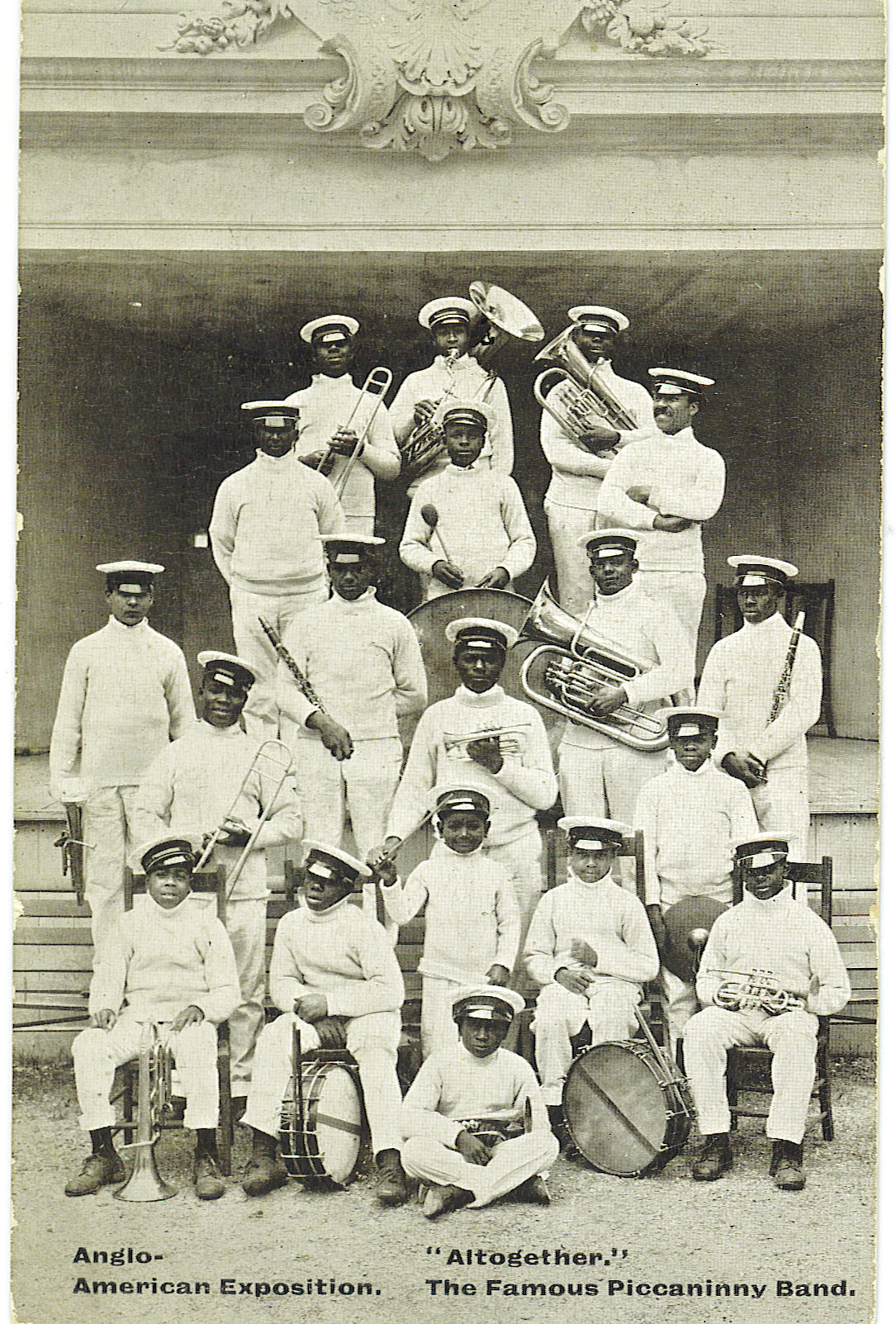

& THE JENKINS ORPHANAGE BAND

Born a slave, Daniel Jenkins left his Barnwell County home in his early 20s to seek his fortunes in Charleston. He took a job delivering lumber, moonlighted as pastor of New Tabernacle Forth Baptist Church, and married Lena James. Yet it was in December 1891, as he delivered lumber to the railroad station one bitterly cold evening, that he realized his true calling, coming upon four starving orphans huddled in a boxcar.

Though he and Lena struggled to keep their own children fed, they took in the homeless boys and asked their church’s congregation to help as much as they could. Soon they were not only caring for these four, but also for dozens of others who could not find a haven within the state’s nine orphanages, all of which had been established for white children.

Thus began Jenkins Orphanage. Within two years, 360 children lived with the Jenkinses. Within two more, nearly 500 children were sheltering in a shed on upper King Street. Jenkins called them his “little black lambs.” In January 1892, he sought permission from the city to use the abandoned Marine Hospital on Franklin Street to house the children. Located behind the Old City Jail and Work House, where once slaves had been severely disciplined for such transgressions as running away or disobeying, the specter, Jenkins said, reminded his charges of what could happen if they left the straight and narrow path.

His church’s donations, even augmented by a small stipend from the city, weren’t enough to keep the children fed, clothed and educated. Though a religious man, Jenkins placed little faith in charity and wanted the children to understand they had to make their own way in the world without counting on help from others. He insisted the orphanage must sustain itself using earned income. He had an idea.

Though people were hesitant to donate money, most seemed amenable to donating old musical instruments. Likewise, Citadel students willingly parted with discarded military uniforms. With that, and the help of two talented musicians who accepted low-paying jobs to teach something they loved, Jenkins’ “little lambs” were poised to be at the forefront of America’s next cultural phenomenon: the great jazz age of the Roaring Twenties.

Soon the boys were not only learning to read music, but also to play all of the donated instruments. Oboes, drums, horns, cymbals – each child was taught to play them all. Wind instruments, Jenkins told Time magazine in a 1935 interview, helped the children stave off tuberculosis.

The boys’ bands soon became a beloved fixture on local street corners. They brought an energy, enthusiasm and spark, with fast-paced syncopated rhythms and irresistible dance moves, unlike anything Charlestonians had ever seen before. After every performance, Jenkins asked for donations and passed his hat among the crowd. It worked. Soon his five bands were impressing audiences all along the East Coast, as well as at the St. Louis World Fair and Anglo-American Exposition. They toured London, giving a command performance for King George. In 1905, they led President Roosevelt’s inaugural parade, as they did again for President Taft four years later.

Jenkins died in 1937 and the orphanage moved to North Charleston two years later. The band played for another decade, but new, somewhat more equitable public subsidies made the need to earn their own living obsolete. By the early 1950s, rock and roll had become the new musical focus. The Jenkins Orphanage Band, like the Roaring Twenties in which they come to international prominence, slipped quietly into history.

The Rev. Daniel Jenkins