WEST POINT RICE MILL

As planning continues for redevelopment of Union Pier, much has been written lately about the site’s Bennett Rice Mill façade. While only one wall remains of that once-magnificent industrial structure, the exterior of another historic mill remains largely intact: that of the West Point Rice Mill off Lockwood Boulevard.

Carolina Gold Rice, the driving force behind Charleston’s 18th and 19th century economies, was laboriously threshed by hand using a mortar and pestle to separate the husk from its kernel until 1787, when Jonathan Lucas invented a water-powered mill that revolutionized how rice was processed.

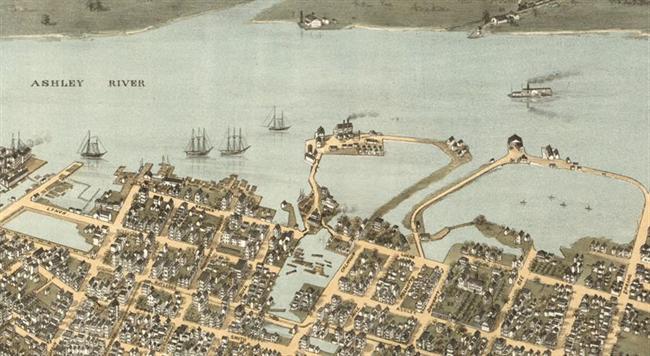

Fifty years later, his grandson, Jonathan Lucas III, built the state’s largest steam-powered rice mill on a lot owned by his father-in-law, Gov. Thomas Bennett Jr., who designed and built Bennett Rice Mill on what’s now Union Pier. Though it’s not known exactly when the West Point mill was completed, Lucas III had begun advertising for coopers by September 1841.

The imposing four-story mill was surrounded by housing for nearly 100 enslaved workers, enough storehouses to hold 40,000 bushels of rice, blacksmith’s and carpenter’s shops, a cooperage that supported 40 barrel makers, wharves, and other supporting buildings.

After Lucas III’s death in 1847, the mill’s revenue supported his children, the eldest of whom, Thomas Bennett Lucas, bought out his siblings’ interests including the land, buildings, equipment, a schooner, and 36 enslaved workers. Following his death in 1858, his family sold the property for $97,000 to a group of investors calling themselves the West Point Rice Mill Company. By March 1860 the mill was operating 24 hours a day, six days a week.

It was a prosperous, if very brief, venture as on Nov. 14, 1860, sparks from a polishing machine ignited a fire, “brilliantly illuminating” the entire west side of the city, according to one newspaper account, and destroying the mill, its ancillary buildings, and more than 23,000 bushels of rice.

Fortunately, the company was insured and immediately began rebuilding. Though unfortunately, this was just weeks before South Carolina seceded from the Union.

Despite the challenges of acquiring building materials during the Union blockade of Charleston Harbor, the company completed a new mill during the bombardment of the city in 1863. Designed in the Greek Revival style, it featured Doric corner pilasters (architectural features that look like columns but are actually part of the wall) and a Palladian window on its eastern façade. Though described as handsome, its architectural merit could not compete with that of the Bennett Rice Mill.

The new facility stored rice during the Civil War but newspaper reports suggest it did not mill any during that turbulent time. Historians generally agree it also stored goods smuggled into the city by blockade runners.

After the war, the mill was occupied by Federal troops and used for food distribution. It began milling rice again after Reconstruction.

Like nearly every masonry structure in Charleston, the mill’s brickwork was damaged in the 1886 earthquake, an event recalled by its earthquake bolts still visible today.

A 1911 hurricane effectively ended what was left of the Lowcounty’s rice industry, after which the mill’s production fizzled out. By 1920, it had closed and sold its machinery to the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan.

The city purchased the 43-acre property in 1926 for $70,000. Several years later, the U.S. Post Office proposed repurposing the mill as a seaplane base for airmail. Though that plan never materialized, it did spawn another idea: as a seaplane terminal and gateway for transatlantic passenger flights between the United States and Germany.

In 1937, the Works Progress Administration began converting the mill into a plane terminal, making major interior changes while leaving the exterior much as it was, though two octagonal smokestacks on its landward façade were removed and a new entry built. Though the first two floors of the renovation were completed, the project was abandoned as the onset of WWII scuttled any partnerships with Germany.

From 1940 through the 1950s, the U.S. Navy used West Point for barracks, mess halls, warehouses and recreation buildings. It later served as offices for organizations including Civilian Conservation Corps, Army Corps of Engineers, and Trident Chamber of Commerce. By 1986, it again sat vacant.

The mill suffered damage in a second fire and Hurricane Hugo, both in 1989, and in 1994 was leased to a private development firm which completed an award-winning $3 million rehabilitation with a first-floor restaurant and offices above. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places a year later.

The mill continues to serve as offices for the firm that rehabbed it and leases office space there. Though the restaurant closed in 2000, the first floor remains an event venue with an outstanding western sunset view.