HAMPTON PARK

Hampton Park is a 60-acre site operated by the City of Charleston and located west of The Citadel along the Ashley River near the northwest corner of the peninsular city. Today cyclists, joggers and dog-walkers enjoy taking laps around the roughly one-mile paved loop that encircles the garden.

Yet the history behind this idylllic site is filled not only with beauty and family sojourns, but also with war, death and destruction. It has served as a pleasure garden, a farm, a siege camp, a racetrack, the center of Charleston's antebellum social life, a horrific POW camp, the site of one of America's first Memorial Day celebrations, a magical Ivory City of hope and economic prosperity, and a failed zoo.

Native American History

No significant archeological findings to date suggest that Native Americans ever established any long-term settlement at what we know today as Hampton Park. That’s not too surprising, given that fewer than 2,000 Natives lived along the state’s coastline before the 18th century, according to author Kevin Eberle, making it easy to space out settlements and hunting grounds.

Lowcountry’s Natives were nomadic and moved around the area in accord with the seasons and availability of their food sources. Summer generally found them along the coast fishing and harvesting shellfish. Women would plant a few rudimentary crops such as corn, sweet potatoes and tomatoes, but never developed any sophisticated cultivation processes. If the seeds they scattered grew, they grew; if not, they didn't. When the weather got cooler in the fall, small, loosely related tribes would move inland to hunt deer and other game before returning to the area of their coastal homes in the spring.

Europeans arrive

At the urging of the Kiawah Indians, the Charles Town colony’s earliest European settlers established their first village in 1670 near the Kiawah settlement at Albemarle Point, just across the Ashley River and a tad north of the neighborhood we associate with Hampton Park today. We know that settlement today as Charles Towne Landing State Park. Here archaeologists have found evidence of post holes and pottery remnants suggesting that the site has been intermittently inhabited since perhaps 500 BC.

A bluff along the east side of the Ashley River features the highest point of land within at least a mile of this area, rising about 22 feet above sea level. Early maps of Charles Town labeled the area as “Indian Hill,” located today just west of The Citadel's Coward Hall.

For many years, local lore held that Indian Hill was a Native American burial ground. That myth was debunked, however, in 1962 by archaeologist Stanley A. South. And while South found no grave remains on Indian Hill, he did find evidence of early colonial settlement, including the foundations of two brick buildings, a wine bottle, pipes, pottery, a nail and a buckle – all probably dating between 1689 to 1720.

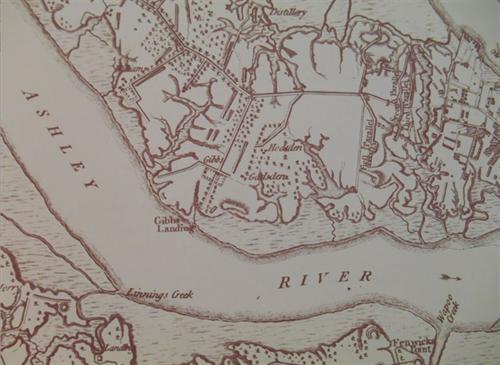

Eberle has traced the earliest documented European ownership of Hampton Park to a land grant of 423 acres given by King Charles to Joseph Dalton, who arrived aboard the Carolina, the first ship to land here in April 1670. About 30 years later, and certainly by the time Edward Crisp created his map of the area in 1711, about 190 acres of Dalton’s land, including Hampton Park, had been acquired by Daniel Cartwright. He in turn sold the tract to John Braithwaite on May 8, 1738.

By 1769, John Gibbes owned the area bounded today by Congress Street on the south and including Hampton Park, the Hampton Park Terrace neighborhood, The Citadel, Lowndes Grove and parts of the Wagener Terrace neighborhood. His plantation became known as Orange Grove or later, just The Grove. Based on a 1780 map (right), Gibbes' main house was located about in front of where Summerall Chapel is today and was surrounded by extensive gardens and supporting buildings.

The American Revolution

Much to Gen. Sir Henry Clinton's frustration, the British were never able to take Charles Town by sea. Therefore he committed to a land attack. On April 1, 1780, leading a large contingent of British soldiers, Clinton set up camp near what today is Grove Street and began bringing his troops over at Gibbes’ Landing. In his journal, a Hessian jager (or sharpshooter), Capt. Johann Ewald, relates that they were posted at Grove Plantation, where he “did picket duty in one of the most beautiful pleasure gardens of the world.”

Fifty years later, in his reminiscences of the Revolution, Gibbes' plantation was described by Alexander Garden, who was the grandson of the botanist for whom the gardenia is named, as well as the husband of Mary Anna Gibbes, John Gibbes’ niece. As Eberle notes, while Garden’s rather romantic account of the war can be somewhat discounted in terms of its accuracy in outlining historical details of the war, his description of Gibbes’ Grove Plantation is nevertheless of value. Orange Grove, he said, had been “improved not only with taste in the disposition of the grounds, but by the introduction of numberless exotics of the highest beauty. [John Gibbes] had, in addition, a green-house and pinery, in the best condition.” (Pinery refers to a hot house specifically for the purpose of growing pineapples.)

The next day, according to Capt. Ewald, “The country around Gibbes’ house has been made a park and depot for the siege, and the greenhouse is a laboratory.” His company was ordered to advance “through the wood in front of Gibbes’ house and through the swamp on the left bank of the Ashley River … The picket was posted in the wood close to Gibbes’ Negro houses.” Ewald later added that Gibbes’ property suffered significant damage as a result: “Major Moncrieff of the Engineers had all the wooden houses in the neighborhood torn down today. From the boards and beams of these he had his men make mantelets (bullet blockers) to be used in building the inner side of the batteries and redoubts and also the cheeks of the embrasures.”

While all this was going on, John Gibbes had been out of town visiting his brother, Robert. When a British soldier named only as Maj. Sheridan arrived at Robert Gibbes’ home, Gibbes asked whether the city had fallen yet. Sheridan, not aware that he was speaking in front of The Grove’s owner, responded “I fear not, but we have made glorious havoc of the property in the vicinity … I yesterday witnessed the destruction of an elegant establishment belonging to a Rebel, who luckily for himself was absent. You would have been delighted to see how quickly the pine apples were shared among our men, and how rapidly his trees and ornamental shrubs were leveled with the dust.”

According to Garden, John Gibbes immediately recognized that Sheridan was talking about his plantation and responded, “I hope that the Almighty will cause the arm of the scoundrel who struck the first blow to wither to his shoulder.” After which, Garden claims, John Gibbes retired to his bed and died.

Gibbes had no children, and so his brother Robert divided the plantation into 27 lots ranging from three to 12 acres each and listed them for sale. Along the northern edge of the property, a large tract (lots 18, 19 & 20) was sold to George Abbot Hall, who developed it into Lowndes Grove Plantation, the same name by which we know it today. According to Hall’s 1791 inventory, the house was built around 1786, four years after the British left Charleston, having destroyed most of what John Gibbes had created.

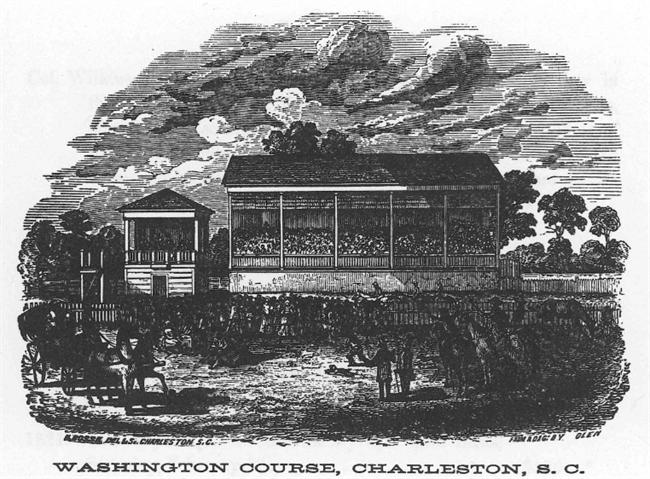

In August of that same year, 1791, the South Carolina Jockey Club purchased the plat we now know as Hampton Park to build a new horse racing track. Like their namesake King Charles II, 18th and 19th century Charlestonians had few greater passions than horse racing. Racing played an important role in Charleston’s social life, and the South Carolina Jockey Club, America’s first, was organized in 1758. Among its elite membership were Gen. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787; Brigadier Gen. William Washington, hero of the Battle of Cowpens; and Gen. William Moultrie, South Carolina governor and Revolutionary War hero. They named the course after William Washington's cousin George, who had visited the city earlier that year. From its first race on February 15, 1792, until its interruption by the Civil War, the course's one-mile loop featured the finest horse racing in the South.

The Jockey Club’s annual Race Week, held each February, marked the pinnacle of Charleston’s social season throughout the antebellum period. Here the great Lowcountry planters gathered to show their horses, make bets, attend balls, seal business deals, drink fine Madeira wine, and introduce their daughters to the right sort of people in the reserved seating section. Race Week was, as Jockey Club historian John Beaufain Irving described it in 1857, the "carnival of the state."

Inns, restaurants and taverns sprung up all around the course. Affluent members of the Jockey Club hosted elaborate dinners and a Friday night ball each year. And rather like today’s Spoleto Festival, the South of Broad crowd would also host grand balls and events for their out-of-town guests with advantageous social connections.

In 1831, the track was enclosed by a 7-foot fence ensuring that only those who paid admission could see the races. Always socially conscious however, the Jockey Club noted that “respectable strangers from abroad or from other states are never allowed to pay admission … they are considered guests.”

Actually watching the horses race was only a part of what made Race Week so special. While ladies generally remained in their designated grandstand, designed by renowned architect Charles Reichart in 1836, the gentlemen wandered the grounds freely, mixing with gamblers, the enslaved, traveling salesmen, and others who were excluded from the more refined areas of the course. The infield and areas surrounding the track provided a range of entertainments and sales opportunities, including public auctions of real estate and slaves. Contemporary news accounts share stories of amusements such as military demonstrations, the “Learned Pig,” whose tricks were advertised in both 1799 and 1804, or the sale of eight thoroughbred horses recently imported from England by a Mr. Porcher.

Though owners occasionally rode their own horses, many of the jockeys were enslaved. Breeders relied on the abilities of their slaves to raise, train and ride their horses.

Col. William Alston, one of the track’s founders, had a cup commissioned sometime after 1810-1811, the date inscribed on it along with his initials and part of the Alston family crest. It has been in the Alston family for eight generations, and according to family lore, was commissioned by Alston after his mare Betsy Baker was victorious over a horse named Rosetta.

Because the track was remotely located (at least as the city existed in the 19th century), it provided a good setting for duels when it was not being used for races. Numerous duels, some fatal, most not, were recorded in local news accounts. In the late 1840s, the Jockey Club purchased a 23-acre farm adjoining the course to provide stabling and pastures for out-of-town guests. When the course wasn’t being used for races or dueling, neighborhood farmers would lease the grounds to graze their livestock.

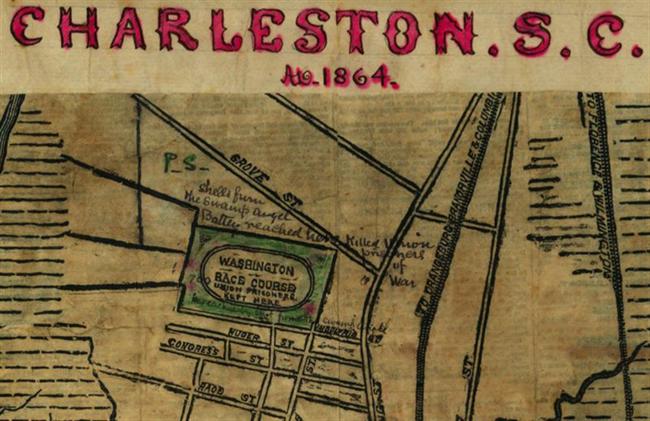

Prisoner of War Camp

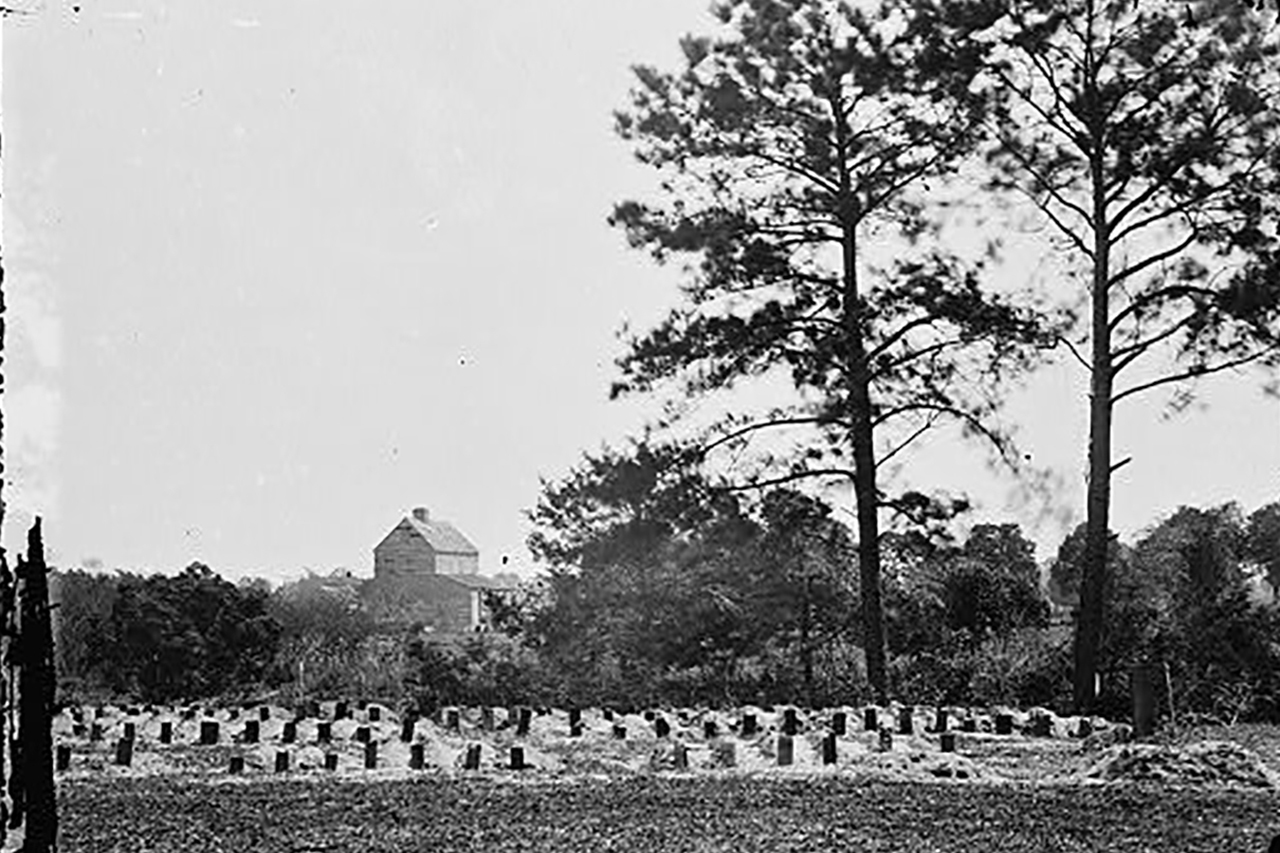

But the fun and games ended with the first shot of the Civil War just weeks after John Cantey’s mare, Albine, won the 1861 heat. The races took a hiatus, and the Washington Course was used to house Union prisoners of war. Officers were quartered in the Ladies Club, once the site of some of Charleston’s most gracious social affairs. Conditions in the open-air camp were horrendous; 257 Union soldiers’ deaths were recorded. They were buried within and around the racecourse in mass unmarked graves.

America's First Memorial Day

After Union forces occupied Charleston, 10,000 (according to the Charleston Daily News) emancipated African Americans marched in a parade to the Washington Race Course to exhume and respectfully rebury the bodies of the Union soldiers who died in the prison camp. They built a fence around the area with an arched gate that read “Martyrs of the Race Course.” They placed flowers on the graves, listened to speakers, spread out blankets and picnicked on the grounds to honor the memory of those who had died fighting for their freedom. Many credit the freedmen’s ceremony at Washington Race Course as America’s first celebration of Memorial Day. The bodies were exhumed and reburied with honors in 1871 at military cemeteries in Beaufort and Florence. The racecourse returned to a pastureland.

The Racecourse Revived

Ten years later, in 1875, the Jockey Club revived the races with more than 100 dues-paying members. Though money was tight, the Club still had two major assets: the track itself and a large cache of valuable Madeira wine that had miraculously escaped discovery by Union troops. Proceeds from the Madeira’s sale helped refurbish the racecourse.

Still, breeding racehorses is a rich man’s sport and few wealthy men were left in Charleston after the War. Grand balls and high style were no longer the order of the day. Race Week had forever lost its cache and attendance dropped. After its last race in 1882, the Jockey Club leased the racecourse, its surrounding pastures, and stables to farmer J.H. West. In 1899, with about two dozen members left, the Club disbanded, donating their remaining assets, including the Washington Course, to the Charleston Library Society.

If the last half of the 19th century was not kind to the S.C. Jockey Club, nor was it to hardly any Charlestonians. The Great Fire of 1861 was followed by four years of bombardment during the Civil War, bankruptcy of the Confederacy, the economic struggles of Reconstruction, the Great Earthquake of 1886, and a string of devastating hurricanes in 1874, 1878, 1885, and two back-to-back in 1893. Charlestonians desperately needed a sense of renewed hope and optimism for the future and that hope came in the form of ...

The South Carolina and West-Indian Exposition

In the last year of the 19th century, a handful of mostly young, enterprising businessmen sought a way to stimulate Charleston’s flagging fortunes, particularly in industry and trade. In colonial times, Charles Town had stood on the western terminus of the great Atlantic coastal highway. Ships dependent on wind power followed the natural trade winds from Europe to the West Indies where they picked up the Gulf Stream currents that conveniently deposited them into Charleston Harbor. With the advent of the steam engine in the 1820s, ships no longer had to rely on these natural navigational resources and Charleston’s port began to lose business. Exposition organizers hoped to “rebrand,” as we might call it today, Charleston as America’s leading port of foreign trade.

A number of grand fairs in such places as London, Atlanta and New Orleans had successfully extolled the virtues of their local goods, talents and commercial resources to the world, and the Charleston group looked to them for ideas and inspiration. Chief among the leaders of the effort was Capt. Frederick C. Wagener, a German immigrant, local businessman, and editor of the Charleston News and Courier.

In 1900, the Library Society rented the old Washington Race Course to the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition. Capt. Wagner, at that time the owner of Lowndes Grove Plantation, added his property to the mix to create about 250 acres. Daily news coverage of the expo exceeded mere hyperbole and served as a powerful marketing tool for the undertaking. After a year of fundraising, the resources were in place to begin planning for Charleston’s 20th century world debut.

Organizers hired Bradford Lee Gilbert, a New York-based architect who had been involved with the Atlanta exposition several years before, to design and oversee construction of the exposition’s elaborate “palaces.” After more than a year of massive construction, the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition opened amid great fanfare on Dec. 1, 1901. Gilbert painted all the buildings, most of which he designed in the exotic Spanish Renaissance style, in a creamy off-white with distinctive contrasting detailing. Thus, the exposition acquired its nickname, “The Ivory City.”

The most prominent among the exhibit halls was the Cotton Palace, at 320 feet long with a grand 75-foot tall dome. Other key buildings included the Hall of Agriculture, Hall of Art, Hall of Commerce, Hall of Fisheries, Hall of Machinery, Hall of Mines and Forestry, Hall for Women, Hall for Negros, Hall of Administration, and the Auditorium. Twenty states were represented, as well as the cities of Cincinnati and Philadelphia, which proudly displayed the Liberty Bell.

Everywhere the grounds were adorned with statuary. The exposition’s popular Midway included a carnival, rides, Eskimo Village, Turkish Parlor, animal acts, exotic dancers, and a House of Horrors. To top it all off, visitors could enjoy the show both day and night, as modern electrical lighting was used throughout the venues. Yet perhaps the Ivory City’s grandest feature was its sunken gardens with its fountains, bridges and pools that ran throughout the venue.

Even so, a plethora of problems plagued the opening of the expo. While Guatemala, Cuba and Puerto Rico were represented, many exhibits from abroad that had been envisioned never materialized. Many exhibits were installed late and hastily. And finally, at the risk of understatement, it was a bad year for weather -- cold, dreary and rainy for Charleston’s subtropical climate, with hurricanes blowing in shortly before the expo’s opening in 1901 and then again in early in June of 1902, hastening its closing.

While organizers considered daily attendance to be good with about 675,000 visitors, including a gala visit from President Theodore Roosevelt, revenues fell far short of expectations. Construction of the Ivory City had cost $1.25 million; receipts were a humble $313,000. Despite the News and Courier’s daily stories touting its grandeur, the expo was a huge financial failure, closing shortly after six months and heavily in debt. Most disappointing, the grand effort lured only two businesses to Charleston: the American Cigar Company and a mattress manufacturer. The Ivory City was quickly dismantled and auctioned off for whatever price its raw materials could bring.

Little remains today of the Ivory City, though a few subtle reminders were left behind. A portion of the Ivory City’s sunken gardens was retained and today serves as the park’s duck pond. A rather small, humble building that had served as the Wayside Inn, an exhibit featuring early American colonial life, was left standing and has been repurposed by the city as administrative office space and storage for the city’s park and horticultural staff.

The old racecourse’s entry posts became surplus property when the parcel was redesigned as Hampton Park. In 1903, August Belmont Jr., a New York racehorse owner and part-time South Carolina resident, asked to buy the four remaining piers. The city of Charleston instead offered them as a gift. The posts were boxed and shipped to New York where they were repaired and reinstalled at the new Belmont Park on Long Island. On Belmont’s opening day, May 4, 1906, nearly 40,000 people streamed through the South Carolina Jockey Club gates at their new New York home.

After the expo’s close, the city of Charleston purchased the Washington Race Course from the Library Society for $32,500, converting it into today’s Hampton Park, named for Wade Hampton III, governor during Reconstruction, United States senator, and the candidate of the Red Shirts, a white supremist paramilitary group that disrupted elections and suppressed black and Republican voting. Hampton was also one of the last members of the South Carolina Jockey Club.

The Zoo

During the mid-20th century, the park featured a small zoo. The first documented references to there being animals at the park were in 1909, and by 1912, yearly city reports listed inventories of the park, including “hoot owls, honey bears, and crocodiles.”

When Archer Huntington of Brookgreen Gardens in Georgetown came to Charleston in 1937, he was so impressed with the park that he gave the city $1,000 and some exotic birds and monkeys that he had living at his plantation. The park added bison, otters and bears. However, the most exciting and exotic animal in the zoo was the lion. In some of his books and articles, author Pat Conroy reminisced about its angry, forlorn roar during his Citadel days. The first lion was donated by a West Ashley man who thought it would be a nifty idea to raise a lion cub.

Families would come to the park with picnics, maybe take in a Citadel parade if possible. Admission to the zoo was free, and the city of Charleston maintained the property with big, open-air spaces. The zoo peaked in the 1940s and ’50s, until desegregation of, and the ensuing white flight from, the city's Upper Peninsula. The less financial support the zoo made through concessions, the shabbier it got.

Unfortunately, the zoo didn't hold up to the standards of the national Animal Welfare Act of 1971. Rather than renovate to improve its facilities, the city decided to close the zoo and repurpose the land. Most of the indigenous animals were sent to Charles Towne Landing. The others were sent to zoos around the country. Few records were kept.

Today

Today the oval, roughly mile-long track of the Washington Race Course has become Mary Murray Boulevard, paved in 1924 by philanthropist Andrew Buist Murray and named for his wife. New gate posts have replaced the ones that are now at Belmont Race Course. In 2007, the Charles and Celeste Patrick family purchased Lowndes Grove, which now serves as a popular event venue. In 2020, Netflix filmed scenes using the house and the area around Hampton Park.